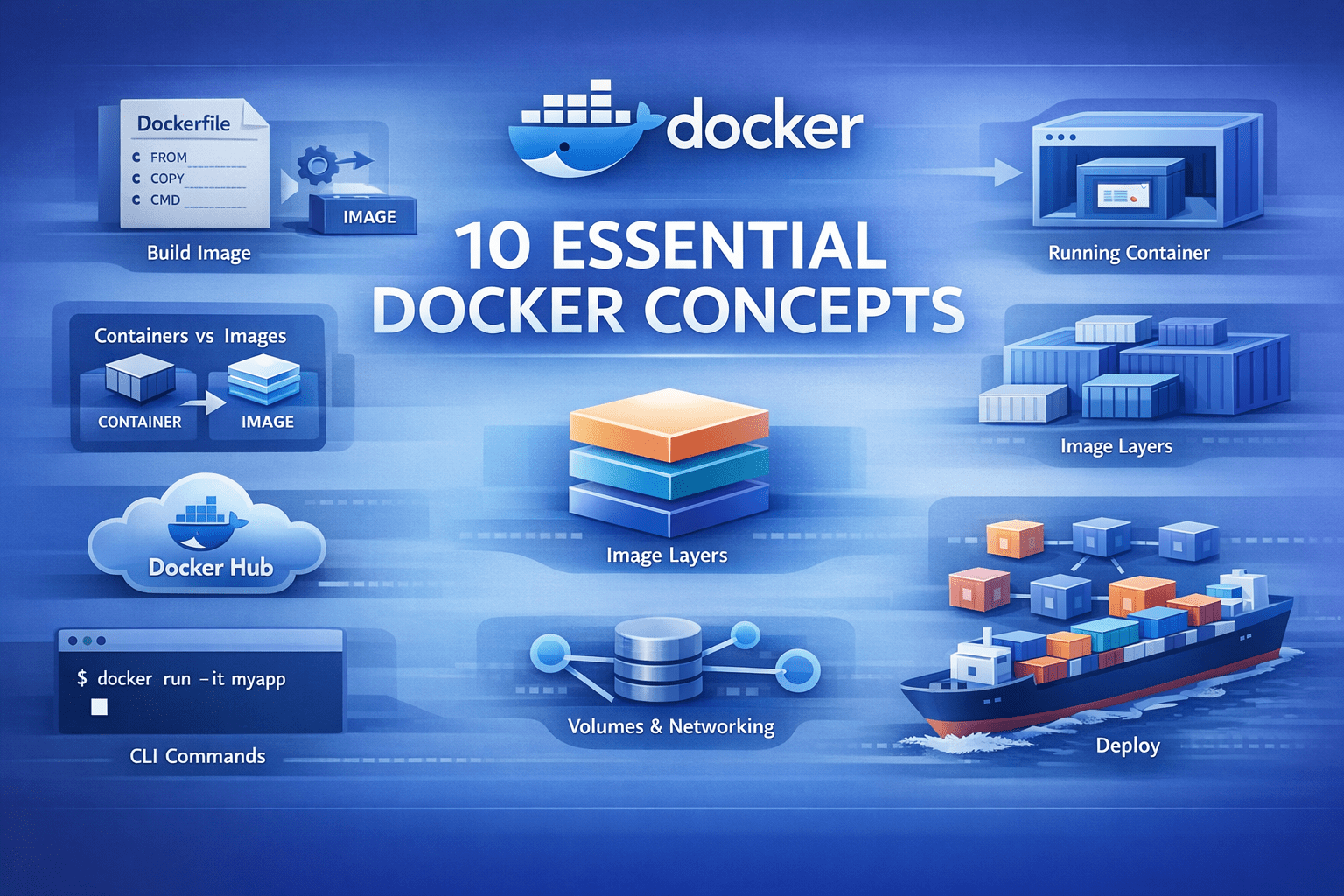

10 Essential Docker Concepts Explained in Under 10 Minutes

Images, containers, volumes, and networks... Docker terms often sound complex to beginners. This quick guide explains Docker essentials to get started.

Image by Author

# Introduction

Docker has simplified how we build and deploy applications. But when you are getting started learning Docker, the terminology can often be confusing. You will likely hear terms like "images," "containers," and "volumes" without really understanding how they fit together. This article will help you understand the core Docker concepts you need to know.

Let's get started.

# 1. Docker Image

A Docker image is an artifact that contains everything your application needs to run: the code, runtime, libraries, environment variables, and configuration files.

Images are immutable. Once you create an image, it does not change. This guarantees your application runs the same way on your laptop, your coworker's machine, and in production, eliminating environment-specific bugs.

Here is how you build an image from a Dockerfile. A Dockerfile is a recipe that defines how you build the image:

docker build -t my-python-app:1.0 .

The -t flag tags your image with a name and version. The . tells Docker to look for a Dockerfile in the current directory. Once built, this image becomes a reusable template for your application.

# 2. Docker Container

A container is what you get when you run an image. It is an isolated environment where your application actually executes.

docker run -d -p 8000:8000 my-python-app:1.0

The -d flag runs the container in the background. The -p 8000:8000 maps port 8000 on your host to port 8000 in the container, making your app accessible at localhost:8000.

You can run multiple containers from the same image. They operate independently. This is how you test different versions simultaneously or scale horizontally by running ten copies of the same application.

Containers are lightweight. Unlike virtual machines, they do not boot a full operating system. They start in seconds and share the host's kernel.

# 3. Dockerfile

A Dockerfile contains instructions for building an image. It is a text file that tells Docker exactly how to set up your application environment.

Here is a Dockerfile for a Flask application:

FROM python:3.11-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

COPY . .

EXPOSE 8000

CMD ["python", "app.py"]

Let's break down each instruction:

FROM python:3.11-slim— Start with a base image that has Python 3.11 installed. The slim variant is smaller than the standard image.WORKDIR /app— Set the working directory to /app. All subsequent commands run from here.COPY requirements.txt .— Copy just the requirements file first, not all your code yet.RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt— Install Python dependencies. The --no-cache-dir flag keeps the image size smaller.COPY . .— Now copy the rest of your application code.EXPOSE 8000— Document that the app uses port 8000.CMD ["python", "app.py"]— Define the command to run when the container starts.

The order of these instructions is important for how long your builds take, which is why we need to understand layers.

# 4. Image Layers

Every instruction in a Dockerfile creates a new layer. These layers stack on top of each other to form the final image.

Docker caches each layer. When you rebuild an image, Docker checks if each layer needs to be recreated. If nothing changed, it reuses the cached layer instead of rebuilding.

This is why we copy requirements.txt before copying the entire application. Your dependencies change less frequently than your code. When you modify app.py, Docker reuses the cached layer that installed dependencies and only rebuilds layers after the code copy.

Here is the layer structure from our Dockerfile:

- Base Python image (

FROM) - Set working directory (

WORKDIR) - Copy

requirements.txt(COPY) - Install dependencies (

RUN pip install) - Copy application code (

COPY) - Metadata about port (

EXPOSE) - Default command (

CMD)

If you only change your Python code, Docker rebuilds only layers 5–7. Layers 1–4 come from cache, making builds much faster. Understanding layers helps you write efficient Dockerfiles. Put frequently-changing files at the end and stable dependencies at the beginning.

# 5. Docker Volumes

Containers are temporary. When you delete a container, everything inside disappears, including data your application created.

Docker volumes solve this problem. They are directories that exist outside the container filesystem and persist after the container is removed.

docker run -d \

-v postgres-data:/var/lib/postgresql/data \

postgres:15

This creates a named volume called postgres-data and mounts it at /var/lib/postgresql/data inside the container. Your database files survive container restarts and deletions.

You can also mount directories from your host machine, which is useful during development:

docker run -d \

-v $(pwd):/app \

-p 8000:8000 \

my-python-app:1.0

This mounts your current directory into the container at /app. Changes you make to files on your host appear immediately in the container, enabling live development without rebuilding the image.

There are three types of mounts:

- Named volumes (

postgres-data:/path) — Managed by Docker, best for production data - Bind mounts (

/host/path:/container/path) — Mount any host directory, good for development - tmpfs mounts — Store data in memory only, useful for temporary files

# 6. Docker Hub

Docker Hub is a public registry where people share Docker images. When you write FROM python:3.11-slim, Docker pulls that image from Docker Hub.

You can search for images:

docker search redis

And pull them to your machine:

docker pull redis:7-alpine

You can also push your own images to share with others or deploy to servers:

docker tag my-python-app:1.0 username/my-python-app:1.0

docker push username/my-python-app:1.0

Docker Hub hosts official images for popular software like PostgreSQL, Redis, Nginx, Python, and thousands more. These are maintained by the software creators and follow best practices.

For private projects, you can create private repositories on Docker Hub or use alternative registries like Amazon Elastic Container Registry (ECR), Google Container Registry (GCR), or Azure Container Registry (ACR).

# 7. Docker Compose

Real applications need multiple services. A typical web app has a Python backend, a PostgreSQL database, a Redis cache, and maybe a worker process.

Docker Compose lets you define all these services in a single Yet Another Markup Language (YAML) file and manage them together.

Create a docker-compose.yml file:

version: '3.8'

services:

web:

build: .

ports:

- "8000:8000"

environment:

- DATABASE_URL=postgresql://postgres:secret@db:5432/myapp

- REDIS_URL=redis://cache:6379

depends_on:

- db

- cache

volumes:

- .:/app

db:

image: postgres:15-alpine

volumes:

- postgres-data:/var/lib/postgresql/data

environment:

- POSTGRES_PASSWORD=secret

- POSTGRES_DB=myapp

cache:

image: redis:7-alpine

volumes:

postgres-data:

Now start your entire application stack with one command:

docker-compose up -d

This starts three containers: web, db, and cache. Docker Compose handles networking automatically: the web service can reach the database at hostname db and Redis at hostname cache.

To stop everything, run:

docker-compose down

To rebuild after code changes:

docker-compose up -d --build

Docker Compose is essential for development environments. Instead of installing PostgreSQL and Redis on your machine, you run them in containers with one command.

# 8. Container Networks

When you run multiple containers, they need to talk to each other. Docker creates virtual networks that connect containers.

By default, Docker Compose creates a network for all services defined in your docker-compose.yml. Containers use service names as hostnames. In our example, the web container connects to PostgreSQL using db:5432 because db is the service name.

You can also create custom networks manually:

docker network create my-app-network

docker run -d --network my-app-network --name api my-python-app:1.0

docker run -d --network my-app-network --name cache redis:7

Now the api container can reach Redis at cache:6379. Docker provides several network drivers, of which you will use the following often:

- bridge — Default network for containers on a single host

- host — Container uses the host's network directly (no isolation)

- none — Container has no network access

Networks provide isolation. Containers on different networks cannot communicate unless explicitly connected. This is useful for security as you can separate your frontend, backend, and database networks.

To see all networks, run:

docker network ls

To inspect a network and see which containers are connected, run:

docker network inspect my-app-network

# 9. Environment Variables and Docker Secrets

Hardcoding configuration is asking for trouble. Your database password should not be the same in development and production. Your API keys definitely should not live in your codebase.

Docker handles this through environment variables. Pass them in at runtime with the -e or --env flag, and your container gets the config it needs without baking values into the image.

Docker Compose makes this cleaner. Point to an .env file and keep your secrets out of version control. Swap in .env.production when you deploy, or define environment variables directly in your compose file if they are not sensitive.

Docker Secrets take this further for production environments, especially in Swarm mode. Instead of environment variables — which can show up in logs or process listings — secrets are encrypted during transit and at rest, then mounted as files in the container. Only services that need them get access. They are designed for passwords, tokens, certificates, and anything else that would be catastrophic if leaked.

The pattern is simple: separate code from configuration. Use environment variables for standard config and secrets for sensitive data.

# 10. Container Registry

Docker Hub works fine for public images, but you do not want your company's application images publicly available. A container registry is private storage for your Docker images. Popular options include:

- Docker Hub (private repositories, limited free tier)

- ECR

- GCR

- ACR

- Self-hosted registries like Harbor or GitLab Container Registry

For each of the above options, you can follow a similar procedure to publish, pull, and use images. For example, you will do the following with ECR.

Your local machine or continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) system first proves its identity to ECR. This allows Docker to securely interact with your private image registry instead of a public one. The locally built Docker image is given a fully qualified name that includes:

- The AWS account registry address

- The repository name

- The image version

This step tells Docker where the image will live in ECR. The image is then uploaded to the private ECR repository. Once pushed, the image is centrally stored, versioned, and available to authorized systems.

Production servers authenticate with ECR and download the image from the private registry. This keeps your deployment pipeline fast and secure. Instead of building images on production servers (slow and requires source code access), you build once, push to the registry, and pull on all servers.

Many CI/CD systems integrate with container registries. Your GitHub Actions workflow builds the image, pushes it to ECR, and your Kubernetes cluster pulls it automatically.

# Wrapping Up

These ten concepts form Docker's foundation. Here is how they connect in a typical workflow:

- Write a Dockerfile with instructions for your app, and build an image from the Dockerfile

- Run a container from the image

- Use volumes to persist data

- Set environment variables and secrets for configuration and sensitive info

- Create a

docker-compose.ymlfor multi-service apps and let Docker networks connect your containers - Push your image to a registry, pull and run it anywhere

Start by containerizing a simple Python script. Add dependencies with a requirements.txt file. Then introduce a database using Docker Compose. Each step builds on the previous concepts. Docker is not complicated once you understand these fundamentals. It is just a tool that packages applications consistently and runs them in isolated environments.

Happy exploring!

Bala Priya C is a developer and technical writer from India. She likes working at the intersection of math, programming, data science, and content creation. Her areas of interest and expertise include DevOps, data science, and natural language processing. She enjoys reading, writing, coding, and coffee! Currently, she's working on learning and sharing her knowledge with the developer community by authoring tutorials, how-to guides, opinion pieces, and more. Bala also creates engaging resource overviews and coding tutorials.