Bringing Machine Learning Research to Product Commercialization

In this blog post I want to share some of the insights into the differences between academia and industry when applying deep learning to real-world problems as we experienced them at Merantix over the last two years.

By Rasmus Rothe, Co-founder at Merantix

Motivation

Last weekend I spent some time back at home with my family and started to reflect about the past couple of years since my time at university, including all the excitement and challenges I experienced during the different stages of my career. Having seen both academic research as well as industry research in the context of deep learning I noticed that there are quite some differences in daily life and methods being applied.

For this reason, in this blog post I want to share some of the insights into the differences between academia and industry when applying deep learning to real-world problems as we experienced them at Merantix over the last two years. Amongst other things, I will go into detail about differences regarding workflow, general expectations as well as performance, model design and data requirements.

Since we started Merantix in 2016, we have incubated multiple growing artificial intelligence ventures in highly interesting, yet challenging industries. This includes healthcare, focusing on automated image diagnosis for mammography, or automotive, providing a scenario-based testing environment for fully autonomous driving software. Besides its ventures, Merantix started a new division in 2018, MX Labs, that is leveraging the capabilities and technology of all other ventures to explore new use cases and develop client-specific solutions together with our partners across many industries.

It is fair to say that we have built a well recognized brand in the research community and also established strong relationships with industry experts and politicians over the last two years. During this time, we had the opportunity to learn our own very important lessons and hence, now feel capable of sharing some of our most relevant insights with you.

A little disclaimer:

- I am covering a list of challenges and learnings that is not exhaustive but gives a structured overview of the major topics, we have been facing across industries.

- The different workflows of academia and industry as described below are a simplified version of the actual processes.

- Though we do mostly supervised deep learning, many challenges and learnings generalize and are applicable for other types of machine learning.

- Maybe not the entire content is new to you but hopefully you can take away at least a few points.

Academia vs industry

When trying to bring deep learning from research into application one can broadly distinguish between commercial and technical challenges. Commercial challenges include obstacles such as getting sufficient access to training data, optimizing product market fit, dealing with law and regulation, and ultimately successfully going to the market. However, this blog post shall mainly focus on the technical side and going forward I will try to refer to industry specific experiences as much as I can.

Most importantly, it is necessary to understand the differences of how academia works compared to industry, i.e. the different requirements and reasons behind them as well as the workflows of the two itself.

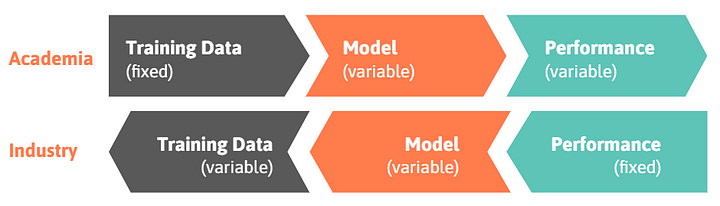

Image: Workflows in academia and industry.

In academia, a researcher typically starts with a fixed training dataset such as MNIST or ImageNet that she wants to train a specific model on. The ultimate goal is to develop novel methods or adapt existing methods in order to improve model performance by some percentage points compared to the current state of the art. By doing so, the researcher establishes a new state of the art in academia and may publish her results in a paper. Whilst being a challenging and tedious process, this workflow is relatively straightforward.

Industry workflows, however, are often the other way around. You start from a fixed performance requirement, let’s say aiming for a 90 - 95% detection of cancers in mammography screenings (there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity) or causing only a single severe accident or disengagement every 1 billion miles. Only then you start to think about deploying a specific model and what kind of training data would be required to sufficiently train that model for the performance requirements. Actually, there is a lot of flexibility with regard to model and data and neither of them have to be state-of-the-art as long as they fulfill the requirements of the use case. However, there might be other constraints such as explainability or fast interference as I will explain in detail below.

All in all, it is crucial to distinguish between academia and industry and especially to keep in mind that the workflows are contrary to each other as illustrated in the figure above. This, in turn, has a lot of implications for how to successfully bring research into application. Hence, I will address some of the insights we gathered at Merantix over the last two years in the three chapters covering 1) performance, 2) model and 3) data.

1. Performance

Hit the binary success criteria

In machine learning driven product development and commercialization it is important to understand that there are rather “binary” success criteria compared to the statistical metrics of academia, which define continuous success in comparison to the current state of the art in research. While in academia a performance of 70% in regard to a specific machine learning task might be a remarkable success (as long as it is better compared to everyone else), commercial applications require the highest degree of functionality and reliability. This, in fact, leads to a partially skewed, biased and irrational perception of artificial intelligence systems today. Accordingly, a single fatal crash of an autonomous Uber vehicle in March 2018 seems to have attracted more attention in the media than 1.3 million road traffic deaths caused by human drivers every single year. This means, even if the machine learning algorithm is on average better than humans at driving cars or detecting cancer, the one fatal crash or false-negative is likely to be perceived as worse. For this reason, it is very important to set the correct scope for production as well as to understand and shape public perception.

Image: Expectation vs. reality.

Define (and limit) the product scope

With regard to the binary success criteria mentioned above there are many machine learning use cases with a very hard threshold of error below which there cannot be any commercial success. This means, there will not be any company selling autonomous vehicles that crash occasionally and no radiologist will ever buy a software that does not detect cancers from time to time - this holds true even if the algorithm outperforms humans on average.

For that reason, setting the right scope and thereby limiting your performance to a certain environment or use case is one of the most crucial steps in machine learning product development. Generally speaking, it is unlikely or extremely ambitious to expect perfect overall performance of your model. However, commercial success depends at least as much on setting the product scope as on the actual neural network performance. Usually, if a machine works equally well or better than a human, it will start to become commercially interesting. However, even for the cases where the performance is not good enough yet, there are two options of adding commercial value:

- Constraining the environment: Leading tech companies and OEMs in the automotive industry execute this strategy by defining a so-called operational design domain (ODD) for autonomous driving. ODD describes operating conditions under which a given driving automation system or feature thereof is specifically designed to function, including, but not limited to, environmental, geographical, and time-of-day restrictions, and/or the requisite presence or absence of certain traffic or roadway characteristics. In other words, by stating that autonomous vehicles will initially be restricted to specific city areas, bus lines or highways they limit the scope of their product and thereby are able to guarantee for a certain performance and reliability.

- Seeing the model as a supporting system: Alternatively, if the performance is not yet good enough for a fully independent and generally applicable product there is the option of selling the model as a decision supporting system as it is quite common in healthcare. So-called computer-aided detection systems (CAD) serve as a “second view” to ensure that radiologists do not miss any suspect area on an image. They do not provide diagnosis, but they are able to analyze patterns, identify and mark suspect regions that may contain an abnormality. In a second step, these marks are then thoroughly inspected and classified by a professional. Another industry where we observe machine learning models as supporting systems is in augmenting customer service and support. Whilst the performance would not be sufficient to completely replace humans, some transitional steps can be taken over and systems can help streamline processes to increase overall efficiency (e.g. augmented messaging, enhanced phone calls, organized email inquiries).

Predict uncertainty

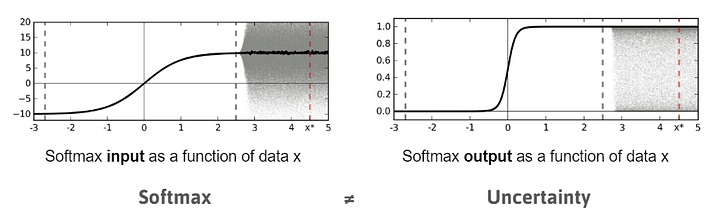

A deep learning model deployed in a practical application will always return a prediction no matter the input. However, for many applications it is useful to also receive an associated uncertainty with the prediction. In the case of medical imaging the algorithm will be able to make a prediction for any kind of input image, while based on the uncertainty it can be decided if a doctor should double-check the result. One might think that softmax probabilities can be used for this as a measure of uncertainty. However, that is a big misconception as it can be seen in the figure for a binary classification problem: passing a point estimate of the mean of a function into a softmax will result in a highly confident prediction. When the distribution (shaded area) is passed through a softmax instead, the average of the output is much lower (more around 0.5).

In traditional machine learning Bayesian techniques have been used when uncertainty played a role. The recently emerging field of Bayesian deep learning is trying to combine the two worlds. Although most of the proposed methods have shown limited results so far and often come with a large computational overhead, the field remains promising and should be monitored closely.

Image: The softmax probabilities are not expressing uncertainty. This can be understood when looking at a distribution of data points and not the mean. Gal & Ghahramani (2015).

Know your target environment

In order to successfully deploy a machine learning system one has to ensure that it will not only work on training sets but also in the real world. In machine learning in order to measure the performance of a model you typically first train it on a distinct training dataset and later use a separate test dataset for evaluation. For the latter, it is crucial that the data is as similar to the real world as possible, hoping the model will also work in practice after succeeding on the test set. However, this process and especially the design of the test datasets can be very difficult as it is necessary to understand the target environment really well, i.e. knowing the relevant context, the dynamic elements and the impact on the environment itself. To elaborate on this issue, let’s consider a few industry examples per category:

- Relevant context: Understanding the relevant context means being aware of all the possible elements, conditions and their outcomes regarding the target environment. In the context of autonomous driving this includes knowing the city, weather, agents and all the other important factors in detail prior to designing the actual test set. In regard to medical vision, this would mean understanding the differences in technology and image qualities as well as the differences between a screening and diagnostics setting.

- Dynamic elements: One step further, understanding the target environment includes all the natural, inevitable changes over time and is therefore not limited to a specific date or point in time. Imagine training and testing a model on an environment only containing horse-drawn carriages. By the time you want to deploy your system there are cars driving on every single street. Whilst this is an oversimplified and exaggerated example, it becomes evident that OEMs and tech companies will need training data that includes autonomous vehicles driving around sooner or later. Medical vision companies on the other side will need to adjust test sets in regard to changes in technical equipment.

- Impact on environment: The impact of the deployed model on the target environment itself is the most challenging aspect of understanding the target environment as it cannot be measured and foreseen easily at the time testing. One example would be the reaction of pedestrians to the increasing presence of autonomous vehicles in their environment. It is conceivable that some pedestrians would be anxious to cross the street at a crossing if they see a fully-equipped autonomous vehicle without any driver. In regard to healthcare and mammography screenings these difficulties could be found when a deployed software puts biases on the radiologists who are using it. Alternatively, as such a solution allows for greater feasibility and accessibility, overall population and distribution might differ over time.

In conclusion, the examples mentioned above imply that it is crucial to continue building new and more accurate test sets due to the changes in data and target environment even if a software is already deployed and operational.

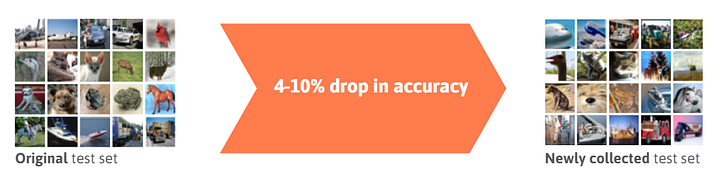

Don’t overfit on your test set

The last insight on performance is once more related to the use of test sets. Research by Recht et al. (2018) has shown that the impressive accuracy of the best performing models might have been driven by the repeated use of the same, unchanging test sets for many years. When collecting a new set of unseen images of CIFAR-10 classifiers to test the model on, which is very similar to the original one regarding its data distribution, there is a large drop in accuracy of 4 - 10% for various previously top performing deep learning models. This demonstrates that the outstanding performance of these models was in many cases based on so-called overfitting - in this case on the test dataset.

Image: Accuracy drops for newly collected test sets.

Coming back to bringing machine learning research into application the results above imply the following: Even in case of a very good test set that adequately represents the real world in accordance to the previous chapter, one always has to take into consideration the possibility of indirectly overfitting to the specific test set after having previously evaluated model performance on the exact same test data - possibly even many times. In order to minimize this risk, it is recommended to evaluate on the “real test set” as little as possible or even just once. If necessary, it is still possible to test on a different validation set and in general it is recommendable to continue updating the test set on a regular basis.

2. Model

Align loss function to business goal

When designing the model it is very important to optimize for the right aspect and aligning the performance metric to the right learning task or business goal, that is, setting the loss function as close as possible to the user’s utility. In the context of trading, for example, instead of optimizing for perfect prediction of the market behaviour, it is actually more useful to design the loss function in relation to profitability. Moreover, in relation to healthcare, instead of aiming for the best possible mass detection accuracy, optimizing for few false-negatives might be most impactful. In the case of breast cancer screening, 97% of all exams are normal. That is why we align the neural network to automatically distinguish suspicious from normal studies, provide structured reports for normal exams without human interaction, filter and forward complex cases to sub-specialist human experts while providing risk based decision support. This process is what we call smart elimination.

Consider unequal cost of misclassification

While no actual costs incur through a research model misclassifying a picture of a dog as a cat, negative consequences in real application can be tremendous. This is especially relevant in healthcare where costs are not only monetary, but also affect a person’s health. The goal of mammography screenings is to detect cancers in asymptomatic women. The potential outcomes of mammography screening are a combination of a women’s health (healthy/ill) and the corresponding diagnosis (positive/negative). Classification is effective when a healthy patient gets a negative diagnosis and an ill patients gets a positive diagnosis. However, classification can fail with unequal negative consequences. If a healthy person gets incorrectly diagnosed with cancer (i.e. false-positive), she will unnecessarily undergo biopsy which can lead to psychological stress and physiological side effects. While these consequences are already serious, mistakenly diagnosing an ill patient as healthy (i.e. false-negative) is even more serious as it dramatically increases mortality.

Make your model explainable

In contrast to the world of academia, where it’s all about performance and accuracy, explainability and transparency matter a lot in industry. In other words, neither the industry nor the regulator like neural network black boxes, i.e. systems containing inputs and outputs without any knowledge of their internal workings. In many cases it can be very difficult to understand the reasons behind an algorithm giving a particular response to a set of data inputs.

Image: Problems with black boxes. A cartoon by Sidney Harris.

Additionally, in some machine learning applications it’s actually not about the model itself but about understanding the underlying system. For example, a company might be more interested in understanding the dynamic and reasons for client churn from a business perspective rather than incrementally optimizing it with machine learning applications.

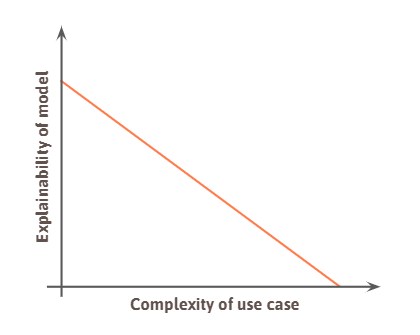

Yet, there is a huge contradiction in regard to the complexity and explainability of neural networks: deep learning is used because the real world cannot be captured with simple rules. In other words, complex use cases require complex models. Hence, it will be very difficult to come up with a simple rule to explain the deep learning system itself. As model complexity is generally anti-proportional to its explainability we often see a trade-off in various use cases.

Image: Complexity-explainability tradeoff.

However, it is noteworthy that there is a growing research field in this area. Visualization of deep neural networks becomes more and more relevant. Using these methods it would be possible to check whether a model actually classified pictures based on the relevant object and not based on a correlated one. For example, we would be able to tell whether a model recognizes boats based on the boat itself and not on the sea surrounding the boat. However one must be careful using these methods. As shown in a recent paper by Adebayo et al. (2018), where they describe a set of randomized experiments to validate these methods, some of the methods may be visually pleasing for humans but do not provide any explanatory power about how the model parameters relate to the input data or the relationship between input data and its labels.

At Merantix, we open-sourced a deep learning visualization toolbox called Picasso last year (Medium Post, Github). As we work with a variety of neural network architectures, we developed Picasso to make it easy to see standard visualizations across our models in different industry applications.

Demo: Picasso visualizer.

Size matters

When designing neural networks for industry applications, model size is another very important aspect to consider due to its impact on performance. In the industry world we face computational as well as connectivity constraints such as limited memory, bandwidth or execution speed. Taking this into consideration, it is obvious that one of the key challenges with regard to complex deep neural networks is to make them run faster and on lower quality hardware without losing significant accuracy. Let’s take autonomous driving once more as an example: if your objective is to identify pedestrians, predict their actions and adjust the car’s driving all in real-time then simplifying and accelerating your models becomes one of the most important tasks to deploy them safely. This is especially true when being restricted by the hardware one can fit into a single car. As a consequence, there is a lot of research currently going on in the field of model compression with the aim of speeding up inference, e.g. Cheng et al. (2017).

State-of-the-art models often not required

Very closely connected to the previous aspect of size and compression, we often made the experience at Merantix that when it comes to model design, the newest, state-of-the-art approaches might not always be the best choice. In fact, many models and applications are overengineered in order to incrementally improve their performance but in a real-world application this improvement might not be worth the time and resources needed to achieve it. Moreover, many times these shiny new methods that look extremely promising on paper are only tested on very simple datasets such as MNIST and fail to work on more difficult and diverse real-world data. Testing on such a small and simple dataset does not only entail the risk of overfitting, but does not guarantee for computational scalability to larger datasets either. In real life and industry applications we care about generalizable models that work in multiple situations and scenarios in order to provide robust and resistant systems. For this reason it is not always useful trying to implement state-of-the-art models and research papers.

3. Data

Consider cost-benefit trade off for data acquisition or labeling

Once the business objective, aspired performance and model design are set, the question of how to assemble the training data arises. Generally speaking, one can distinguish between three kinds of data: 1) existing and labeled data, 2) existing but unlabeled data and 3) missing data.

With regard to the first type, the already labelled data, it is necessary to figure out what kind of sampling strategies shall be executed and which specific dataset the model shall be trained on. Concerning the second type, one has to decide what part of the existing data shall be labeled, e.g. for training. In situations in which unlabeled data is abundant but manual labeling is expensive, it is possible to make use of techniques such as “active learning”, i.e. trying to figure out which unlabeled data, when labeled, would provide the biggest information gain to the model and improve it the most. This specific field of research actually gained a lot of traction over the last two years as people realized that there might be nearly infinite data in some industries such as autonomous driving so that figuring out what data is the most relevant remains one of the biggest challenges. Hence, by integrating active learning techniques it is possible to reduce the cost of training data acquisition without compromising on model performance and accuracy. Lastly, in regard to the missing data, one needs to evaluate the costs and benefits of collecting more data while ultimately trying to cover most of the blind spots and corner cases.

Focus on rare samples

Especially in the real world, dealing with data means dealing with class imbalance. That means in real-world datasets some events are extremely rare - the so-called edge or corner cases. These rare examples are very hard to collect yet again leading to high costs of data acquisition. Still, they are crucial when trying to solve the last 1% of the most difficult machine learning tasks such as autonomous driving or cancer detection (see our related Medium Post).

Image: Autonomous vehicles should be prepared for all kind of (un)likely scenarios.

As mentioned earlier, there are binary success criteria when bringing machine learning applications into product development. In order to roll out fully autonomous vehicles, for example, the algorithm must be capable of dealing with all kinds of conceivable scenarios and risks and therefore also cover the long tail of edge cases. Yet, these cases are very difficult to collect or record in the real world making testing and validation a very challenging, slow and expensive process. One approach we use at Merantix to mitigate these difficulties is scenario-based testing. It describes a methodology to test end-to-end autonomous vehicle software stacks offline on a catalog of thousands of very short driving scenarios. These scenarios can be based on real world log or simulation data and are very carefully defined and organized. The idea is to take human driving capabilities, such as performing unprotected left turns or overtaking cyclists as a starting point, and subsequently very specifically curate scenarios which test these capabilities on a full software stack. Scenario based testing is used by many industry leaders such as Waymo or Uber. It is uniquely useful because it accelerates development, optimizes resource usage and is truly scalable to vast amounts of test cases, vehicles and engineers.

Get high quality annotations

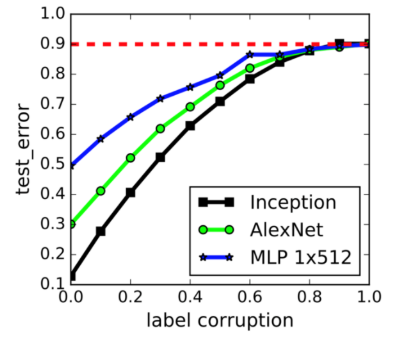

The last important aspect I want to highlight in regard to data is the quality of annotations. As labels are likely to be noisy, especially when created by humans, it is necessary to be very careful when labeling the data and monitoring their quality from the beginning as well as on a regular basis. The reason behind that amount of effort and attention is the huge impact noise has on overall model performance. As shown in the graph below, only small percentages of label corruption lead to quite significant test error rates.

Image: Error effects of label corruption. Zhang et al. (2017).

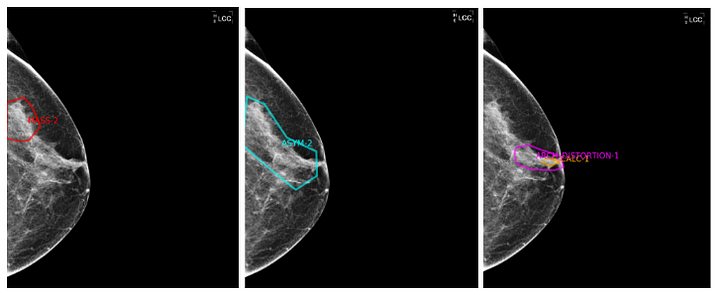

While label corruption can be easily mitigated for simple tasks that have a ground truth, i.e. provable objective data (comparable with the gold standard in medicine and statistics), it becomes increasingly difficult for complex tasks such as medical image interpretation. When a mammogram is performed, the breast is, with the help of X-rays, projected onto a 2-dimensional black and white image which contains much less information than the reality itself. Accordingly, ground truth for a malignant case cannot easily be defined in mammography images and can only be provided by an examination of the tissue extracted through biopsy. Unfortunately, biopsy proven studies are scarce, hard to acquire and do not exist for all kind of use cases. Additionally, the difficulty of reading mammography images per se can lead to dramatic interpretation variability by radiologists as well as high levels of label noise.

Image: Reader variability across radiologists for an identical image.

At Merantix, we’ve implemented numerous processes and checks that help us minimize reader variability and label noise. Radiologists go through an individual training where they learn the comprehensive annotation guidelines. Once the training is completed every radiologist needs to pass a sample dataset test in order to start annotating for our company. Furthermore, we have developed an automatic benchmark which continuously monitors and compares the quality of the annotators with their peers. Finally, we have created a script that flags studies for control if annotations differ from the results in the retrospective radiological reports.

Conclusion

In this blog post I shared various learnings that demonstrate the differences between academia and industry in machine learning as well as some insights we gathered at Merantix when applying deep learning to real-world problems. What I would like you to take away from this blog post is that the workflows of the two worlds, academia and industry, are actually contrary to each other resulting in different implications and requirements for overall performance, model design and datasets. I strongly hope that some of the ideas and approaches mentioned above might be helpful and applicable for other people who plan to use deep learning in their business. Please feel free to reach out to me if you have any comments or questions! If you are excited about applying deep learning to real-world problems consider joining us in Berlin. We are hiring!

Acknowledgements

- Sebastian Spittler for assisting me in writing this article.

- Robert, Florian, Maximilian and Thijs for providing valuable inputs.

- Clemens and John for reviewing and giving feedback on this article.

Bio: Rasmus Rothe is one of Europe's leading experts in deep learning and a co-founder at Merantix. He studied Computer Science with a focus on deep learning at ETH Zurich, Oxford, and Princeton. Previously he launched howhot.io as part of his PhD research, started Europe's largest Hackathon HackZurich and worked for Google and BCG.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- Applying Deep Learning to Real-world Problems

- 3 Stages of Creating Smart

- How to Make AI More Accessible