BIG, small or Right Data: Which is the proper focus?

BIG, small or Right Data: Which is the proper focus?

For most businesses, having and using big data is either impossible, impractical, costly to justify, or difficult to outsource due to the over demand of qualified resources. So, what are the benefits of using small data?

By Dr. Ricardo Baeza-Yates, CTO, NTENT

We find ourselves in the era of big data, where vast, continuous streams of heterogeneous human-related data are collected by digital means, and simplified for consumption according to the 5V characterization: Volume (size of the data), Variety (diversity of the content), Velocity (the rate it’s produced), Veracity (the quality of the content) and Value (it’s business impact). These humongous data sets are collected via many different means including computer networks, social media profiles, web browsing histories, mobile phone sensors, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, video data from (self-)driving and robotic applications, our commercial transactions and more.

The complex task of processing and analyzing big data has pushed computer engineering and computer science on several fronts, such as distributed parallel processing (e.g., map-reduce and streaming architectures) and machine learning (e.g., deep learning). It has challenged our technological limits in data center design, computer processing, storage capacity and communication bandwidth. Although big data still has many significant research problems, sometimes the solution is just more data. However, for most institutions, having and using big data is either impossible, impractical, costly to justify, or difficult to outsource due to the over demand of qualified resources.

But what exactly is small data? This question has been asked and answered so frequently it has multiple definitions: “Data that is small enough size for human comprehension” [1], “data that fits in a laptop” [2], “data in a volume and format that makes it accessible, informative and actionable” [3]; “the digital trace that each person generates” [4]. For our purposes, all of these definitions are appropriate since they exclude big data applications.

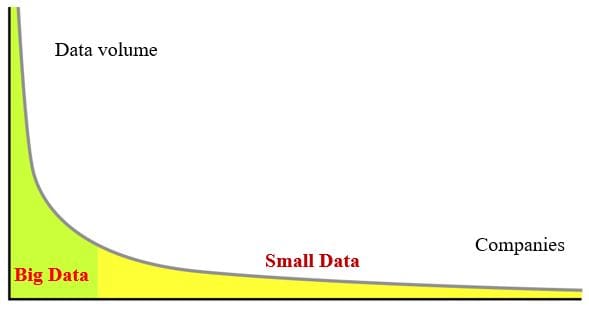

The most important reason to worry about small data is that most companies in the world will never have big data. Displayed graphically below, with companies plotted in one axis and the amount of data that they can gather in the other, we see that data generated by most companies forms the torso and the diverse long tail of data at large.

Big data has the benefit of malleability, meaning we can use big data to generate small data. One of the most common purposes of big data is to produce myriads of coherent, specialized small data sets, often created just from the transformation process itself. Some key benefits of small data include:

- Most data that people consume is small data;

- In most cases, small data is the right data for the problem at hand [5];

- Small data is more available, precise, and complete;

- Small data is driving the Internet of Things [6];

- Small data is about people, small groups, and communities;

- Small data describes every person in each context;

- Small data can be understood and interpreted by humans;

- Most innovations are triggered by small data [7].

For the reasons above there appears to be larger Value in small data. Some people claim that “small data is the new big data” [7, 8], that “small data is the real revolution” [2] or that “small data is where the money lies” [9]. In fact, extremely small data contributes to our yes-or-no-decisions for any important choice, making how much data we need to determine a given decision a primary concern. However, having less data does not imply the problem is simpler or that we exactly know what to do with it [10]. First ask yourself a few questions:

Which type of data do I need? How much data do I really need? What is the best I can do with the data I have?

Your answers should prompt more complicated, subtler questions like:

What are the privacy issues on the data? Can I solve the problem in my smartphone? Is there any data bias and if so, how can I compare my results to other people’s results?

At best, currently we have partial answers to these questions. However, many research problems beckon better answers or have no answers at all. Among them are privacy preservation, resource-efficient machine learning, adaptive and dynamic model selection, overfitting analysis, feature selection, specialized smoothing, error analysis, bias detection and calibration, better interpretability and causation analysis.

In addition, while processing small data should be faster, in most cases there isn’t enough data to apply deep learning, spawning new problems such as bias, noise detection and correction, quantifying error and uncertainty, constrained modeling, and smoothing. To make matters worse, these problems have interdependencies with trade-offs that in most cases are not well studied. If we factor in that most target data is personal and lives in a tiny, portable device, then we must preserve privacy and/or resolve the problem in a device that has limited computing power, memory, communication, and energy.

Therefore, due to small data’s ubiquitous presence and large impact in the world of SMEs and individuals, it is crucial to understand it well. In addition to the 5V characterization of volume, velocity, variety, veracity, and value, we should mention some other notable aspects [11]:

- Scope - How exhaustive is the data related to the problem at hand?

- Resolution and Identity - How fine-grained is the data and how identifiable is each item?

- Relational - How easy is it to conjoin different datasets through common fields or encodings that are part of the data?

- Flexibility - How easy is it to extend the data (g., adding new fields) and scale in size?

- Privacy - How does the data relate to people?

Table 1 compares small data with big data using 12 dimensions. Additional aspects of data might be important for most applications, including how data is collected, the technology and software used, the data ontology employed, and the context in which the data is generated [12].

Lately, the use of small data has awakened interest among the scientific e-health community. Deborah Estrin [4] defines small data as “the picture of your personal health.” She spearheads initiatives that liberate data to the consumer, arguing that digital behavior leads to valuable knowledge about an individual’s personal health (e.g., http://smalldata.io/). Patients may opt to share certain data with researchers and analysts while keeping other information solely for their doctor, or choose not to disclose any data at all. Researchers and practitioners should follow a framework of informed consent to guarantee the only data exchanged is the data authorized by the patient. In some cases, the patient can be reticent to share her sensitive personal information. In those cases (maybe the most interesting ones) digital devices should be able to analyze the data locally, triggering an alarm only in case of emergency

In this and other contexts, small personal data refers to information related to a living individual. Such data is normally associated with an identifiable person and might include first name, middle name, last name, address, telephone number, passport number, specific health or cognitive conditions, etc. In general, this data is private and hence the regulatory environment with respect to privacy, data protection and security is pivotal.

As a side effect, there are two facts that make the use of personal data challenging for machine learning based applications. First, it is difficult to gather; personal data is considered private or sensitive and most people are not comfortable sharing it. Second, personal data related to mental, health and educational conditions is scarce because such conditions are infrequent, and often “hidden,” meaning they are not identified before the symptoms. Furthermore, most of these conditions (e.g., physical and mental illnesses, education disorders) are very much subject dependent. Their manifestations highly depend from person to person, making generalizations impossible. This means that data coming from some subjects might not be suitable training data for other individuals. As a result, the most suitable data to train an algorithm is the data belonging to the same subject, making the target data even smaller.

Clearly more research is needed in addition to our current efforts at big data advances like the two main trends of distributed/parallel processing, and deep learning. We also need to explore the limits of small data and exacting its uses. Then we can learn if the right data, needs to be small or big. However, if 2013 was considered the year of small data [13], we are already late. Don’t wait another minute. Now is the perfect time to perfect it.

| Characteristic | Small data | Big data |

| Data sources | Traditional enterprise data, user studies, personal data | Social media, sensor data, log data, device data, video, images |

| Volume | Up to Gigabytes | Terabytes or more |

| Velocity | Slow: batch to real time, not always a fast response is needed | Fast: often real time, immediate response needed |

| Variety | Structured, semi-structured, unstructured | Unstructured, structured, multi-structured |

| Veracity | Easier | Harder |

| Value | Business intelligence, analysis and reporting | Complex, advanced, predictive business analysis and insights |

| Scope | Partial: small populations, samples | Exhaustive: continuous streams, entire populations |

| Privacy | Usually private | Private but also anonymous |

| Density | Coarse to dense | Dense |

| Identity | Weak to Precise | Precise |

| Relations | Weak to strong | Strong |

| Flexibility | Low to Middle | High |

Table 1. Comparison of characteristics of small data and big data (partly based in [11]).

REFERENCES

[1] jWork.org (2014). "Small data". Never heard this term? URL: http://jwork.org/main/node/18.

[2] R. Pollock (2013). Forget Big Data, Small Data is the Real Revolution. URL: http://blog.okfn.org/2013/04/22/forget-big-data-small-data-is-the-real-revolution.

[3] WhatIs. URL: http://whatis.techtarget.com/search/query?q=small+data. Last access: August 2016.

[4] D. Estrin (2014). Viewpoint: small data, where n=me, Communications of ACM 57 (4), 32-34. Based in the TEDMED 2013 presentation: What happens when each patient becomes his or her own “universe” of unique medical data? URL: http://www.tedmed.com/talks/show?id=17762.

[5] R. Baeza-Yates (2013). Big data or right data? In Proceedings of International Workshop on Foundations of Data Management, CEUR Proceedings, vol. 1087.

[6] M. Kavis (2015). Forget Big Data: Small data is driving the Internet of Things. URL: http://www.forbes.com/sites/mikekavis/2015/02/25/forget-big-data-small-data-is-driving-the-internet-of-things/#3635c7f0661b.

[7] M. Lindstrom (2016). Small data: The tiny clues that uncover huge trends. St Martin’s Press, NY, USA.

[8] Wharton (2016). Why Small Data is the new big data. URL: http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/small-data-new-big-data/

[9] F. Shilmover (2015). Forget Big Data: Small Data is where the money lies. URL: https://www.datanami.com/2015/05/20/forget-big-data-small-data-is-where-the-money-lies/.

[10] A. El Deeb (2015). What to do with “small” data. URL: https://medium.com/rants-on-machine-learning/what-to-do-with-small-data-d253254d1a89#.w01mkrich (Accessed August 2016).

[11] R. Kitchin (2013). Big data and human geography: Opportunities, challenges, and risks. Dialogues in Human Geography 79(1), 1-14.

[12] R. Kitchin and T. Lauriault (2015). Small data in the era of big data. GeoJournal 80, 463-475.

[13] Small Data Group (2013). The Year of Small Data. URL: https://smalldatagroup.com/2013/12/11/the-year-of-small-data/.

Bio: Dr. Ricardo Baeza-Yates is currently CTO of NTENT, a search technology company based in Carlsbad, California, since June 2016; as well as Director of Computer Science Programs (part-time) of Northeastern University, Silicon Valley campus, since January 2018.

Related:

BIG, small or Right Data: Which is the proper focus?

BIG, small or Right Data: Which is the proper focus?