The Notebook Anti-Pattern

This article aims to explain why this drive towards the use of notebooks in production is an anti pattern, giving some suggestions along the way.

By Kristina Young, Senior Data Scientist

In the past few years there has been a large increase in tools trying to solve the challenge of bringing machine learning models to production. One thing that these tools seem to have in common is the incorporation of notebooks into production pipelines. This article aims to explain why this drive towards the use of notebooks in production is an anti pattern, giving some suggestions along the way.

What is a notebook?

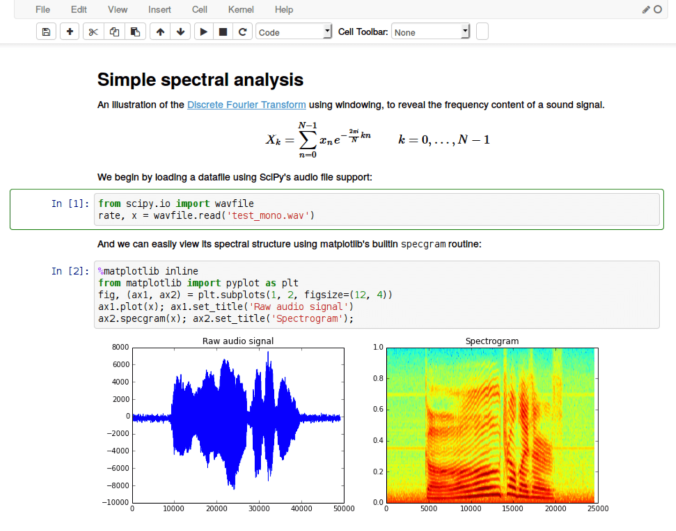

Let’s start by defining what these are, for those readers who haven’t been exposed to notebooks, or call them by a different name.

Notebooks are web interfaces that allow a user to create documents containing code, visualisations and text. They look as follows:

What are notebooks good for?

Contrary to what you might have gathered from the introduction, Notebooks are not all bad. They can be quite useful in certain scenarios, which will be described in the sub-sections below.

Data analysis

This is probably their most common use. When greeted by a new dataset, one needs to dig into the data and do certain visualisations in order to make sense of it. Notebooks are good for this because they allow us to:

- quickly get started

- see the raw data and visualisations in one place

- have access to many existing cleaning and visualisation tools

- document our progress and findings (which can be extracted as HTML)

Experimentation

When it comes to machine learning, a lot of experimentation takes place before a final approach to solve a problem is chosen. Notebooks are good to play around with the data and various models in order to gain an understanding of what works with the give data and what does not.

One time tasks

Notebooks are also a good playground. Sometimes one needs to perform an automated task once whilst perhaps not being familiar or comfortable with writing bash or using other similar tools.

Teaching or technical presentations

When teaching python, or performing a technical presentation for your peers, you may want to show code and the result of that code immediately after. Notebooks are great for this as they allow you to run code and show the result within the same document. They can show visualisations, represent sections with titles and provide additional documentation that may be needed by the presenter.

Code assessments

If your company provides code challenges to candidates, notebooks can be a useful tool. This also depends on what your company needs to assess. Notebooks allow a candidate to combine documentation, explanations and their solution into a single page. They are also easy to get running for the assessor, provided that the candidate has given the package requirements. However, what they cannot provide is a wide enough assessment of the candidate’s understanding of software engineering principles, as we will understand better from the next section.

What are notebooks bad at?

A lot of companies these days are trying to solve the challenge of bringing models to production. Data scientists within these companies may come from very varying backgrounds, including: statistics, pure mathematics, natural sciences and engineering. One thing that they do have in common is that they are generally comfortable with using notebooks for analysis and experimentation, as the tool is designed for this purpose. Because of this, large companies that provide infrastructure have been focusing on bridging the “productionisation gap” by providing “one click deployment” tools within the Notebook ecosystem, therefore encouraging the use of notebooks in production. Unfortunately, as notebooks were never designed to serve this purpose to begin with, this can lead to unmaintainable production systems.

The thought of notebooks in production always makes me think of the practicality of a onesie comic – looks beautiful but is very impractical for certain scenarios.

Now that we know what Notebooks can do well, let’s dive into what they are really bad at in the following sections.

Continuous integration (CI)

Notebooks are not designed to be automatically ran or handled via a CI pipeline, as they were built for exploration. They tend to involve documentation and visualisations, which would add unnecessary work to any CI pipeline. Though they can be extracted as a normal python script and then ran on the CI pipeline, in most cases you will want to run the tests for the script, not the script itself (unless you are creating some artefact that needs to be exposed by the pipeline).

Testing

Notebooks are not testable, which is one of my main pain points about them. No testing framework has been created around these because their purpose is to be playgrounds, not production systems. Contrary to popular belief, testing in data products is just as important and possible as in other software products. In order to test a notebook, the code from the notebook needs to be extracted to a script, which means that the notebook is redundant anyway. It would need to be maintained to match the code in the extracted script, or diverge into some more untested chaos.

If you want to learn more about testing ML pipelines, check out the article: Testing your ML pipelines.

Version control

If you have ever had to put a Notebook on git or any other version control system and open a pull request, you may have noticed that this pull request is completely unreadable. That is because the notebook needs to keep track of the state of the cells and therefore has a lot of changes taking place behind the curtains when it is ran to create your beautiful HTML view. These changes also need to be versioned, causing the unreadable view.

Of course you may be in a team that uses pairing and not pull requests, so you may not care about the pull request being unreadable. However, you lose another advantage of version control through this readability decrease: when reverting code, or looking into old versions for a change that may have introduced or fixed a problem, you need to rely purely on the commit messages and manually revert to check a change.

This is a well known problem of notebooks, but also one that people are working on. There are some plugins that can be used in order to alleviate this at least in a web view of your version control system. One example of such a tool is Review Notebook App.

Collaboration

Collaboration in a notebook is hard. Your only viable collaboration option is to pair, or take turns on the notebook like a game of Civilization. This is why:

- Notebooks have a lot of state being managed in the background, therefore working asynchronously on the same notebook can lead to a lot of unmanageable merge conflicts. This can be a particular nightmare for remote teams.

- All the code is also in the same place (other than imported packages), therefore there are continuously changes to the same code, making it harder to track the effect of changes. This is particularly bad due to the lack of testing (explained above)

- The issues already mentioned in version control above

State

State has already been mentioned in both of the above, but it deserves its own point for emphasis. Notebooks have a notebook wide state. This state changes every time that you run a cell, which may lead to the following issues:

- Unmanageable merge conflicts within the state and not the code itself

- Lack of readability in version control

- Lack of reproducibility. You may have been working in the notebook with a state that is no longer reproducible because the code that lead to that state has been removed, yet the state has not been updated.

Engineering standards

Notebooks encourage bad engineering standards. I want to highlight the word encourage here, as a lot of these are things are avoidable by the user of the notebook. Anti-patterns that are often seen in notebooks are:

- Reliance on state: Notebooks rely heavily on state, especially because they generally involve some operations being performed on the data in the first few cells in order to feed this data into some algorithm. Reliance on state can lead to unintended consequences and side-effects throughout your code.

- Duplication: One cannot import one notebook into another, therefore when trying multiple experiments in different notebooks one tends to copy paste the common pieces across. Should one of these notebooks change, the others are immediately out of date. This can be improved by extracting the common parts of the code and importing them into the separate notebooks. Duplication is also seen a lot within the notebooks themselves, though this is easily avoidable by just using functions.

- Lack of testing: One cannot test a notebook, as we have seen in the above testing section.

Package management

There is no package management in notebooks. The notebook uses the packages installed in the environment that it is running in. One needs to manually keep track of the packages used by that specific notebook, as different notebooks running in the same environment may need different packages. One suggestion is to always run a new notebook in a fresh virtual environment, keeping track of that specific notebook’s requirements separately. Alternatively all the notebooks in an environment would rely on a single requirements file.

So what can we do?

Great, so now we know why notebooks in production are a bad idea and why we need to stop dressing up experimentation tools as productionization tools. Where does that leave us though? That depends on the skills and structure of your team. Your team most likely consists either of:

- Data scientists with engineering skills

- Or, data scientists focused on experimentation and ML/data engineers bringing models to production

So let’s take a look at the two scenarios below.

A team of data scientists with engineering skills

In this scenario, your data science team is in charge of the models end to end. That is, in charge of experimentation as well as productionization. These are some things to keep in mind:

- You may keep using notebooks for the experimentation if that is a preferred tool, but move away from these when:

- Collaborating

- Bringing the model anywhere outside of your playground

- Learn from existing software engineering frameworks and principles

- Check out some of these tools and architectures, which may help you design your infrastructure or just provide inspiration (be careful, sometimes a notebook option is available – it’s a trap!):

Separation of engineering and data science skills

Some larger organisations prefer more specialised skillsets, where data scientists work on the experimental work and ML/data engineers bring those to production. The points listed in the above scenario are still relevant, but I have 1 additional suggestion specific to this scenario:

Please, please, please Don’t throw the model over the fence! Sit together, communicate and pair/mob program the pipeline into production. The model doesn’t work unless it provides value for the end users.

Conclusion

Like with any tool, there are places to use notebooks and places to avoid using them in. Let’s do one last recap for these.

| Good | Bad |

| Data analysis | Continuous integration |

| Experimentation | Testing |

| One time tasks | Version control |

| Teaching/technical presentations | Collaboration |

| Code assessments | State |

| Engineering standards | |

| Package management |

In conclusion, there are two messages that I would like you to take from this article:

- To the ML practitioner: notebooks are for experimentation, not for productionization. Stick to software engineering principles and frameworks for bringing things to production, they have been designed from past learnings which we should be leveraging.

- To the people creating tooling: We appreciate you working on making things easier for everyone ♥ , but please move away from the notebook anti-pattern. Focus on creating easier to use tools that encourage positive software engineering patterns. We want:

- Testability

- Versioning

- Collaboration

- Reproducibility

- Scalability

Bio: Kristina Young is a Senior Data Scientist at BCG Digital Ventures. She has previously worked at SoundCloud as a Backend and Data Engineer in the Recommendations team. Her previous experience is as a consultant and researcher. She has worked as a back end, web and mobile developer in the past on a variety of technologies.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- Testing Your Machine Learning Pipelines

- Automatic Version Control for Data Scientists

- Easy, One-Click Jupyter Notebooks