Why You Should Start Using .npy Files More Often

In this article, we demonstrate the utility of using native NumPy file format .npy over CSV for reading large numerical data set. It may be an useful trick if the same CSV data file needs to be read many times.

Introduction

Numpy, short for Numerical Python, is the fundamental package required for high performance scientific computing and data analysis in Python ecosystem. It is the foundation on which nearly all of the higher-level tools such as Pandas and scikit-learn are built. TensorFlow uses NumPy arrays as the fundamental building block on top of which they built their Tensor objects and graphflow for deep learning tasks (which makes heavy use of linear algebra operations on a long list/vector/matrix of numbers).

Many articles have been written demonstrating the advantage of Numpy array over plain vanilla Python lists. You will often come across this assertion in the data science, machine learning, and Python community that Numpy is much faster due to its vectorized implementation and due to the fact that many of its core routines are written in C (based on CPython framework). And it is indeed true (this article is a beautiful demonstration of various options that one can work with Numpy, even writing bare-bone C routines with Numpy APIs). Numpy arrays are densely packed arrays of homogeneous type. Python lists, by contrast, are arrays of pointers to objects, even when all of them are of the same type. You get the benefits of locality of reference.

In one of my highly cited articles on Towards Data Science platform, I demonstrated the advantage of using Numpy vectorized operations over traditional programming constructs like for-loop.

However, what is less appreciated is the fact, when it comes to repeated reading of the same data from a local (or networked) disk storage, Numpy offers another gem called .npy file format. This file format makes incredibly fast reading speed enhancement over reading from plain text or CSV files.

The catch is — of course you have to read the data in traditional manner for the first time and create a in-memory NumPy ndarray object. But if you use the same CSV file for repeated reading of the same numerical data set, it makes perfect sense to store the ndarray in a npy file instead of reading it over and over from the original CSV.

What is this .NPY file?

It is a standard binary file format for persisting a single arbitrary NumPy array on disk. The format stores all of the shape and data type information necessary to reconstruct the array correctly even on another machine with a different architecture. The format is designed to be as simple as possible while achieving its limited goals. The implementation is intended to be pure Python and distributed as part of the main numpy package.

The format MUST be able to:

- Represent all NumPy arrays including nested record arrays and object arrays.

- Represent the data in its native binary form.

- Be contained in a single file.

- Store all of the necessary information to reconstruct the array including shape and data type on a machine of a different architecture. Both little-endian and big-endian arrays must be supported and a file with little-endian numbers will yield a little-endian array on any machine reading the file. The types must be described in terms of their actual sizes. For example, if a machine with a 64-bit C “long int” writes out an array with “long ints”, a reading machine with 32-bit C “long ints” will yield an array with 64-bit integers.

- Be reverse engineered. Datasets often live longer than the programs that created them. A competent developer should be able to create a solution in his preferred programming language to read most NPY files that he has been given without much documentation.

- Allow memory-mapping of the data.

Demo using simple code

As always, you can download the boiler plate code Notebook from my Github repository. Here I am showing the basic code snippet.

First, the usual method of reading the CSV file in a list and converting that to an ndarray.

import numpy as np

import time

# 1 million samples

n_samples=1000000

# Write random floating point numbers as string on a local CSV file

with open('fdata.txt', 'w') as fdata:

for _ in range(n_samples):

fdata.write(str(10*np.random.random())+',')

# Read the CSV in a list, convert to ndarray (reshape just for fun) and time it

t1=time.time()

with open('fdata.txt','r') as fdata:

datastr=fdata.read()

lst = datastr.split(',')

lst.pop()

array_lst=np.array(lst,dtype=float).reshape(1000,1000)

t2=time.time()

print(array_lst)

print('\nShape: ',array_lst.shape)

print(f"Time took to read: {t2-t1} seconds.")

>> [[0.32614787 6.84798256 2.59321025 ... 5.02387324 1.04806225 2.80646522]

[0.42535168 3.77882315 0.91426996 ... 8.43664343 5.50435042 1.17847223]

[1.79458482 5.82172793 5.29433626 ... 3.10556071 2.90960252 7.8021901 ]

...

[3.04453929 1.0270109 8.04185826 ... 2.21814825 3.56490017 3.72934854]

[7.11767505 7.59239626 5.60733328 ... 8.33572855 3.29231441 8.67716649]

[4.2606672 0.08492747 1.40436949 ... 5.6204355 4.47407948 9.50940101]]

>> Shape: (1000, 1000)

>> Time took to read: 1.018733024597168 seconds.

So this was the first time read, which you have to do anyway. But if you are likely to use the same dataset many more times, then, after your data science process is finished, don’t forget to save the ndarray object in .npy format.

np.save('fnumpy.npy', array_lst)

Because if you do so, the next time, reading from the disk will be blazing fast!

t1=time.time()

array_reloaded = np.load('fnumpy.npy')

t2=time.time()

print(array_reloaded)

print('\nShape: ',array_reloaded.shape)

print(f"Time took to load: {t2-t1} seconds.")

>> [[0.32614787 6.84798256 2.59321025 ... 5.02387324 1.04806225 2.80646522]

[0.42535168 3.77882315 0.91426996 ... 8.43664343 5.50435042 1.17847223]

[1.79458482 5.82172793 5.29433626 ... 3.10556071 2.90960252 7.8021901 ]

...

[3.04453929 1.0270109 8.04185826 ... 2.21814825 3.56490017 3.72934854]

[7.11767505 7.59239626 5.60733328 ... 8.33572855 3.29231441 8.67716649]

[4.2606672 0.08492747 1.40436949 ... 5.6204355 4.47407948 9.50940101]]

>> Shape: (1000, 1000)

>> Time took to load: 0.009010076522827148 seconds.

It does not matter if you want to load the data in some other shape,

t1=time.time()

array_reloaded = np.load('fnumpy.npy').reshape(10000,100)

t2=time.time()

print(array_reloaded)

print('\nShape: ',array_reloaded.shape)

print(f"Time took to load: {t2-t1} seconds.")

>> [[0.32614787 6.84798256 2.59321025 ... 3.01180325 2.39479796 0.72345778]

[3.69505384 4.53401889 8.36879084 ... 9.9009631 7.33501957 2.50186053]

[4.35664074 4.07578682 1.71320519 ... 8.33236349 7.2902005 5.27535724]

...

[1.11051629 5.43382324 3.86440843 ... 4.38217095 0.23810232 1.27995629]

[2.56255361 7.8052843 6.67015391 ... 3.02916997 4.76569949 0.95855667]

[6.06043577 5.8964256 4.57181929 ... 5.6204355 4.47407948 9.50940101]]

>> Shape: (10000, 100)

>> Time took to load: 0.010006189346313477 seconds.

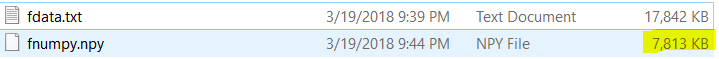

It turns out that at least in this particular case, the file size on disk is also smaller for the .npy format.

Summary

In this article, we demonstrate the utility of using native NumPy file format .npy over CSV for reading large numerical data set. It may be an useful trick if the same CSV data file needs to be read many times.

Read more details about this file format here.

If you have any questions or ideas to share, please contact the author at tirthajyoti[AT]gmail.com. Also you can check author’s GitHub repositories for other fun code snippets in Python, R, or MATLAB and machine learning resources. If you are, like me, passionate about machine learning/data science, please feel free to add me on LinkedIn or follow me on Twitter.

Bio: Tirthajyoti Sarkar is a semiconductor technologist, machine learning/data science zealot, Ph.D. in EE, blogger and writer.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- Why You Should Forget ‘for-loop’ for Data Science Code and Embrace Vectorization

- Working With Numpy Matrices: A Handy First Reference

- Getting Started with Python for Data Analysis