I wasn’t getting hired as a Data Scientist. So I sought data on who is.

I wasn’t getting hired as a Data Scientist. So I sought data on who is.

Instead of focusing on skills thought to be required of data scientists, we can look at what they have actually done before.

By Hanif Samad, Data Scientist

At the time I’m writing this, every single trending article in my Towards Data Science home page is talking about applying or learning a particular skill in data science. Every single one. At the top are big-picture skills such as How to Work With Stakeholders as a Data Scientist and How to Become a Data Engineer, followed by a litany of very specific skills including technical primers on Batch Gradient Descent vs. Stochastic Gradient Descent, Multi-Class Text Classification, Faster R-CNN, et cetera. As a dedicated Medium platform for “sharing concepts, ideas, and codes” in data science, it is not surprising that such learning resources attain high popularity amongst Towards Data Science followers, who are probably navigating data-centric projects and professions. But to a novice looking to prioritize what is essential, it can quickly become daunting. Should one train to become a master Kaggler? Apply neural networks in image recognition or Natural Language Processing? Neither? How about Kubernetes and learning to deploy models, since it’s all about putting models into production? And whatever the hell happened to Hadoop?

My LinkedIn profile describes me as a Software Engineer and Data Scientist. Based on my job history, the first half of that pair is probably more accurate, as I’ve only ever secured short-term contract gigs in data science. Having voluntarily moved out of an earlier career as a healthcare statistician, I was becoming vexed with my attempts to land a full-time data scientist position where I’m based, which is Singapore. I’ve seen some acquaintances, with only a Bachelor’s degree, readily secure positions while my Master’s in Medical Statistics and General Assembly certificate in Web Development did not seem to land the knockout blow that I hoped they would (two out of three in the Conway Venn diagram, or so I thought). My patience was also wearing thin with some of the “How I landed such-and-such role”-type self-congratulatory advice running rampant online which, after all, admitted a sample size of just 1.

What was dawning on me was that I had conflated the practice of data science with the strategy to become part of it. To my surprise, these turned out not to be the same thing. Like most novices, I was putting together information from a haphazard mix of blog posts, the requirements section of data science job postings, and hearsay from people in the field. The skills-heavy focus of these sources, not to mention the castigating and often moralizing tone that data scientists can and should learn a whole bunch of things, can ironically entrap beginners in a never-ending cycle of chasing after the latest skills, when perhaps the most efficient strategy would be to quickly land an adjacent data-related position first and then learn the skills on the job.

Daniel Kahneman would call this an example of falling victim to the availability heuristic. I think that I need to acquire 10 impossible skills before breakfast because that’s what I’ve read about how a data scientist looks like, without pausing to consider that there are probably thousands of data scientists out there who have already been successfully hired, and most of them (by definition) are not superstars. What I needed was not another navel-gazing post on the top skills required of a data scientist but actual data on people who have successfully made the transition into data science. What were they doing before?

What I needed was… actual data on people who have successfully made the transition into data science

Data on Data Scientists

While there are some publicly available, large-scale surveys that have been conducted on who is a data scientist, I saw several problems with such data:

- Self-selection bias. Because these surveys are affiliated with certain kinds of organizations and are completely voluntary, a certain profile of respondents might be over-represented in the sample. I saw a particular problem with over-enthusiastic TensorFlow practitioners dominating the Kaggle Data Science Survey, which might be very different from how data science is actually practiced in business.

- Respondent bias. Being completely voluntary and having no feedback on the respondent (you don’t suffer any consequence from misrepresenting yourself), individual respondents might have fewer disincentives to inflate their titles or education or other kinds of data.

- Market representation. My main motivation was to find out the profiles of people who have actually been successfully hired as data scientists in my target market (Singapore). From what I’ve seen, the survey data is inundated with data science aspirants (mainly students), and specific data on data scientists based in Singapore was limited.

There was no question in my mind that LinkedIn was where I needed to get the data from. While there might still be some selection bias (LinkedIn’s algorithms might not be showing me a truly random sample of data scientists¹), I saw its widespread adoption by jobseekers and the recruitment industry alike as an inbuilt check to minimize respondent bias and ensure the truthfulness of its profiles. LinkedIn profiles are subject, as it were, to the coercions of the actual job market.

In addition, LinkedIn allows me to specify the geography of profiles that I wished to analyze in my search query, limiting it to Singapore if so desired. There was only one problem: getting the data itself.

Scraping the data: don’t say I didn’t warn you

There has been some controversy surrounding the legality of scraping LinkedIn data. While recent precedent establishes that such information is public and therefore amenable to extraction by anyone, the legal status is far from settled. In any case, there are several roadblocks you will encounter when you try to scrape LinkedIn data:

- You will be in violation of LinkedIn’s User Agreement. While the enforceability of such contracts remains murky, you run the risk of having your account suspended for breaching the terms of service.

- LinkedIn sets an upper limit to the number of profiles you can click on within the free tier, which your little selenium bot will quickly hit (especially if you’re spending a lot of time just debugging the scraper).

- LinkedIn has been quietly and frequently changing their HTML tags such that scraping based on any current set of tag attributes has a rather short shelf life.

Suffice to say the scraper that I wrote remained useful for long enough to acquire a decently sized dataset (1027 LinkedIn profiles) before the tags were replaced and the code became outdated. (If you’d like to find out more about the code nonetheless, feel free to reach out to me²).

Using the search query “Data Scientist AND Singapore”, I extracted as many profiles as I could from the People section of LinkedIn. There were really only three data elements that I considered relevant: Current Position (job title and name of employer), Education (most recent institution and field of study) and Experience (position, organization, and duration of previous roles). Limiting myself to these three elements not only saved time in writing and debugging the scraper but was also my attempt at minimizing the scope of potential liabilities from not adhering to LinkedIn’s terms of service.

After filtering out data science aspirants, students, and profiles with insufficient information, I was left with 869 data scientist profiles. Now I can go about asking: what common traits do currently employed data scientists have?

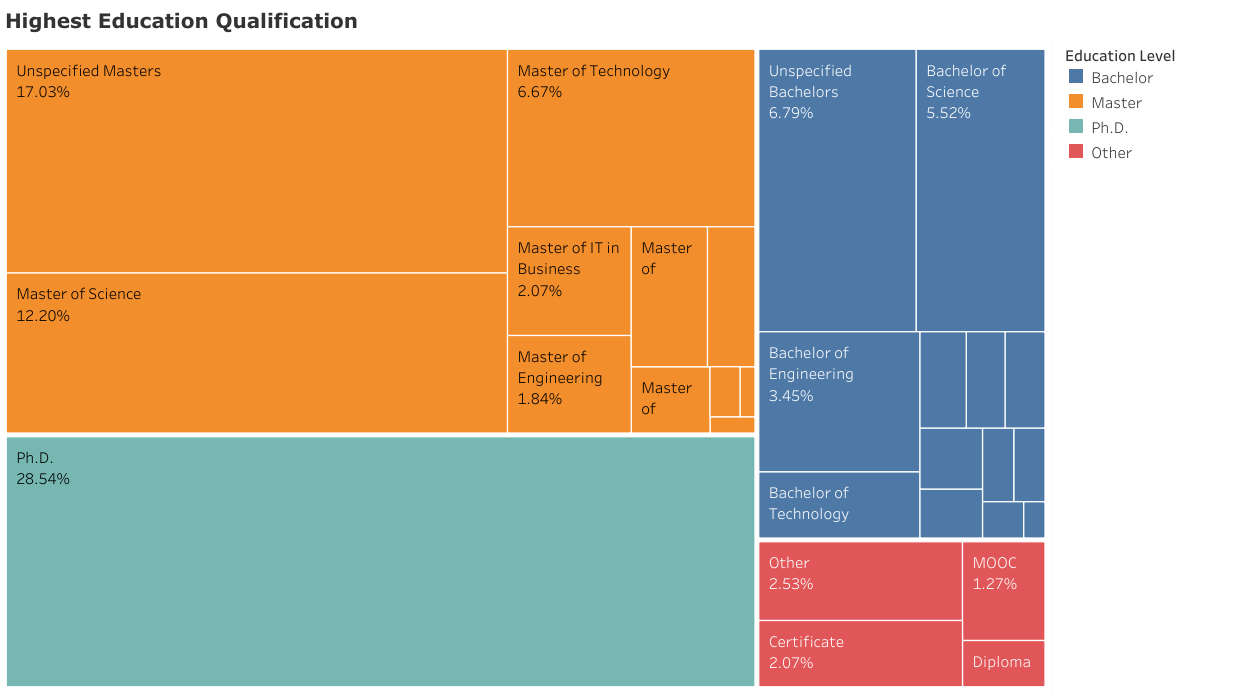

Finding 1: most data scientists have postgraduate degrees

The most striking finding from the data, and which has been corroborated elsewhere, is that most (73%) currently employed data scientists have degrees beyond just a Bachelor’s. A plurality (44%) hold a Master’s degree, while Ph.D.s outrank Bachelor’s degrees 29% to 21%. Only 6% of data scientists reported some form of MOOC, bootcamp or non-traditional certification as their primary qualification. This suggests that prospective employers trust the signaling provided by an advanced degree to fulfill the complex requirements of the data scientist position. It also puts paid to the notion that data science bootcamps or other non-traditional certification programs are an adequate substitute for such degrees.

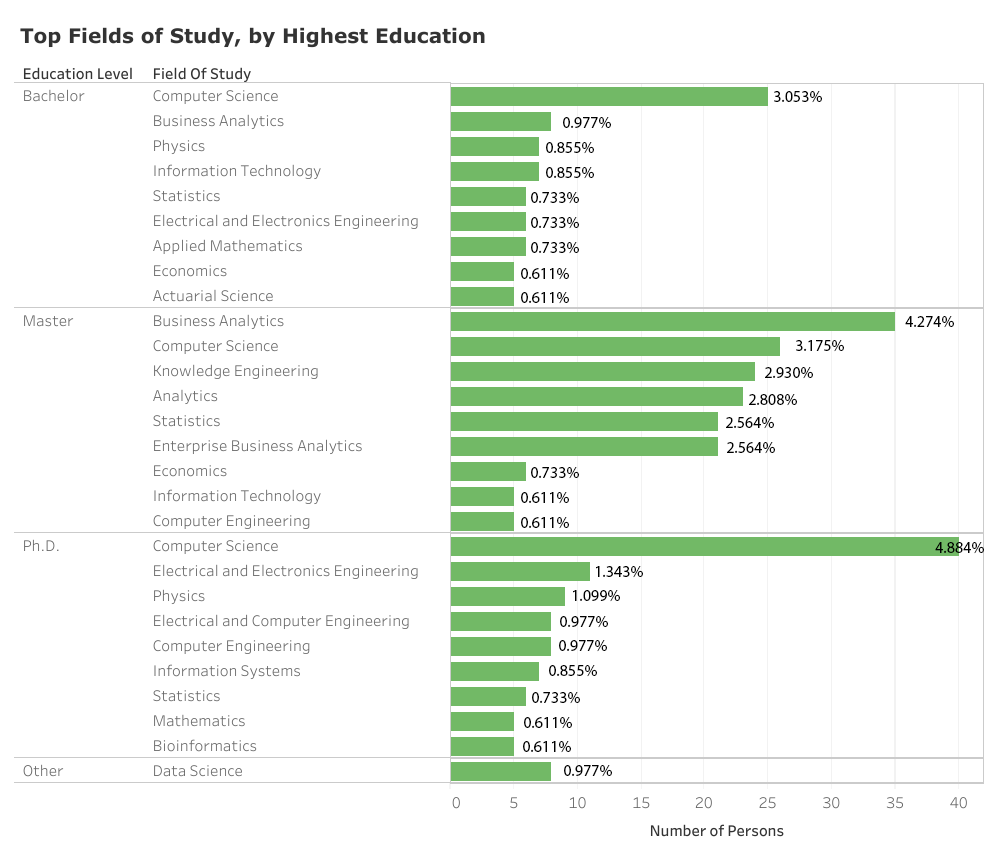

Finding 2: Computer Science and Engineering, but also Business Analytics dominate fields of study

The common conception of a triumvirate of Computer Science, Mathematics and Statistics, and Engineering disciplines forming the bedrock of a data science career is somewhat borne out by the data. However, there are differences. Computer Science by far trumps all other singular fields, accounting for 14% of all studied disciplines. Engineering is a diverse category and includes such disparate fields as Chemical, Electrical and Electronics, and so-called Knowledge Engineering, and cumulatively accounts for 22% of studied disciplines. Mathematics and Statistics are also represented under various guises, including Applied Mathematics, Mathematical Physics, and Statistics and Applied Probability, but seem to carry less heft and cumulatively account for only about 12% of studied disciplines. A surprising winner in the data science education stakes is Business Analytics and other Analytics fields, which collectively account for 15% of disciplines. It is, in fact, the top-ranked field for data scientists who report having a Master’s degree as their highest qualification.

Other highly ranked fields include Physics (3.5%) and Information Technology (2.2%). The picture that emerges is that while computing- and engineering-related fields have demonstrated continuing relevance for becoming a data scientist, mathematics and statistics are somewhat being eclipsed by the newer business-oriented field of Analytics (and its variants). Nevertheless, a very long tail of other fields represents the broad diversity of disciplines that have been pursued by current data scientists.

Finding 3: Currently employed data scientists tend to be in mid-career positions

The modal years of reported work experience for a data scientist in this sample is between 4–6 years, depending on their highest level of qualification. This may seem blindingly obvious, but it is perhaps worth repeating that most data scientist hires are not college graduates straight out of their heroic MOOC conquests, which sometimes seems to be the impression given by blog posts about how to break into the field. As with most other open positions, the average person filling that position will probably be someone with experience.

As an additional fun fact, none of the data scientists reporting non-traditional certification programs were fresh hires, having at least 1 year of work experience prior.

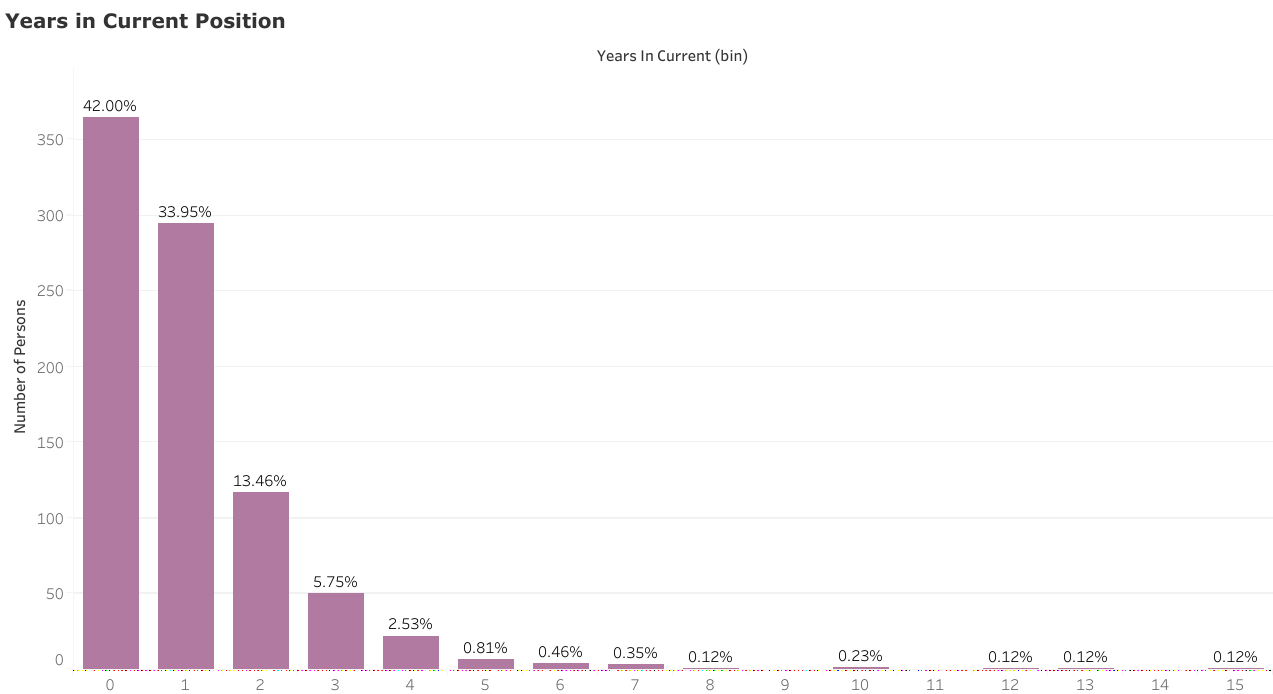

Finding 4: Most data scientist positions are new

Another data point corroborating the above finding is that most data scientists (76%) have occupied their current positions for less than 2 years, with a plurality (42%) holding it for less than a year. This suggests that while most data science job openings have been relatively recent, the people filling them up nevertheless have been in the job market for a while.

Finding 5: Researcher, Software Engineer, Analyst or Data Science Intern? Good. Existing data scientist? Even better.

Finding out what data scientists were doing immediately prior to their current positions was the core insight I wanted to get to. Perhaps unsurprisingly (given the preponderance of postgraduate degree holders in the sample) a good chunk (11%) of them report being Scientists or Researchers (including Research Assistants and Research Fellows) previously. An equivalent chunk (11%) reported some form of Software Engineering position, including developers and solution architects. Another section of data scientists were previously Analysts (11%) in their various forms, including Data Analysts and System Analysts. Interestingly, interns and trainees (11%) are also a viable class of precursors to a full-fledged data scientist role, and they typically take the form of Data Science or Analytics internships. Other highly ranked previous positions include Consultancy (5%), various Managerial positions (5%), and Data Science Instructorship (3%).

Unremarkably, nothing beats already being a Data Scientist in attempting to land a new data science role. Fully 28% of the sample reported Data Scientist as a previous position. Furthermore, this incumbency advantage appears to be increasing — for example, 29% of hires who have been 1 year or less on the job reported Data Scientist as their previous position compared to only 12% of hires who have stayed between 3–4 years on the job.

For myself, it was worth noticing that Statisticians and Actuaries are at the bottom of the heap as a prior role for existing data scientists.

Finding 6: Half of data scientist roles come from non-technology companies

While well-funded, mature technology companies (such as Google or Amazon) tend to get the limelight in terms of desirable places to get hired as a data scientist, it is worth noting that nearly half (49%) of data scientists in this sample came from places that do not directly create technology products. These tended to be companies and institutions from finance and insurance (11%), consulting (9%), government (5%), manufacturing(5%), and academia (2.4%). Within the technology category, industries that are well-represented include transportation (8%, primarily due to Singapore-based ride-hailing app Grab), enterprise (8%, including IBM, SAP, and Microsoft), e-commerce (5%) and finance (5%). Here we see the distinction between a financial institution like DBS Bank hiring for data scientists versus a fintech company like Refinitiv using data science to create technology products for such institutions.

There is a sizeable category of technology companies I have labelled as AI & ML (6.5%). This includes companies like DataRobot with a track record of delivering actual automated machine learning products, but also newer outfits like Amaris.AI.

It would be far too convenient if this cleavage between non-technology and technology companies of data scientists neatly aligns with the Type A vs Type B data scientist characterization proposed elsewhere, as it suggests that the job market (at least in Singapore) has been pretty equitable in providing opportunities for either type. Nevertheless, this would be an interesting and valuable hypothesis to test.

Conclusion: What does this all mean for me?

If you are serious about landing a data scientist position, rather than fretting about what kind of skills you need from reading random blog posts, it is perhaps more helpful to get a sense of who exactly has been successful at it. The most frequent combination of traits would probably be someone with a Master’s or Ph.D. in Computer Science, Engineering, Mathematics or Analytics; who’s been employed in industry for about 4–6 years; and was a Researcher, Software Engineer, Analyst or Data Science Intern in a previous life². However, don’t make the fallacy of thinking that it is this combination which constitutes the majority of data scientists, as it represents a multiplication of probabilities (which may themselves not be independent). As this piece and other research have noted, the background of data scientists is incredibly diverse, more so than other kinds of positions such as Software Engineer. Nevertheless, the picture that emerges is that certain profiles do tend to be favoured and the amount of ‘standing out’ that is expected of your resumé will probably be proportional to how much it deviates from such profiles.

Finally, I would note that while the data is silent on the necessity of skills acquired from non-traditional certifications such as MOOCs and bootcamps, it does suggest something about their sufficiency: they clearly aren’t. A postgraduate degree is a far better indicator of your prospects as a data science hire. This is not to suggest that acquiring such skills is unimportant; data science is moving at a rapid pace and many of the most important algorithms and techniques will not be covered by a conventional academic syllabus. It is merely to suggest that the acquisition of specific skills may be answering a need other than your immediate employability as a data scientist.

A myriad of specialized courses on data science has been proliferating that seem designed to prey on the insecurities of aspirants, who’ve been told again and again they need just that particular combination of skills to achieve a breakthrough. Understanding data on who actually gets hired as a data scientist throws a cold, hard splash of reality to such existential considerations.

Notes

¹ If there is any reason to poke holes at the data, it would be to doubt the representativeness of the sample. LinkedIn only displays profiles that have at least a 3rd-degree connection to you, and the profiles might have been sorted by a non-random algorithm (my scraper extracted the top profile results in order). There is a case to be made that I am not optimally connected to obtain a truly random sample of data scientists from my target market (e.g. not having enough hub nodes in my network). Getting more profiles from other LinkedIn accounts and doing a sensitivity analysis would throw more light on this question.

² All the visualizations in this piece (and more) have been put together in a Tableau Story called “Who is a Data Scientist in Singapore?”. If you have any substantive questions about the data or code, do consider the response section of this post, or write an email and send it to admin@hanifsamad.com.

UPDATE Aug 5, 2019: There seems to be a fair bit of interest in the code that I used to scrape the data. I am currently working on a follow-up post to share this with those of you who are keen. Stay tuned.

Bio: Hanif Samad is a statistician, software engineer, data scientist in Singapore. He is focused on the problems worth solving.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- If you’re a developer transitioning into data science, here are your best resources

- Top 13 Skills To Become a Rockstar Data Scientist

- The secret sauce for growing from a data analyst to a data scientist

I wasn’t getting hired as a Data Scientist. So I sought data on who is.

I wasn’t getting hired as a Data Scientist. So I sought data on who is.