Geometric foundations of Deep Learning

Geometric foundations of Deep Learning

Geometric Deep Learning is an attempt for geometric unification of a broad class of machine learning problems from the perspectives of symmetry and invariance. These principles not only underlie the breakthrough performance of convolutional neural networks and the recent success of graph neural networks but also provide a principled way to construct new types of problem-specific inductive biases.

By Michael Bronstein (Imperial College), Joan Bruna (NYU), Taco Cohen (Qualcomm), and Petar Veličković (DeepMind).

This blog post is based on the new “proto-book” M. M. Bronstein, J. Bruna, T. Cohen, and P. Veličković, Geometric Deep Learning: Grids, Groups, Graphs, Geodesics, and Gauges (2021), Petar’s talk at Cambridge, and Michael’s keynote talk at ICLR 2021.

In October 1872, the philosophy faculty of a small university in the Bavarian city of Erlangen appointed a new young professor. As customary, he was requested to deliver an inaugural research program, which he published under the somewhat long and boring title Vergleichende Betrachtungen über neuere geometrische Forschungen (“A comparative review of recent researches in geometry”). The professor was Felix Klein, only 23 years of age at that time, and his inaugural work has entered the annals of mathematics as the “Erlangen Programme” [1].

Felix Klein and his Erlangen Programme. Image: Wikipedia/University of Michigan Historical Math Collections.

The nineteenth century had been remarkably fruitful for geometry. For the first time in nearly two thousand years after Euclid, the construction of projective geometry by Poncelet, hyperbolic geometry by Gauss, Bolyai, and Lobachevsky, and elliptic geometry by Riemann showed that an entire zoo of diverse geometries was possible. However, these constructions had quickly diverged into independent and unrelated fields, with many mathematicians of that period questioning how the different geometries are related to each other and what actually defines a geometry.

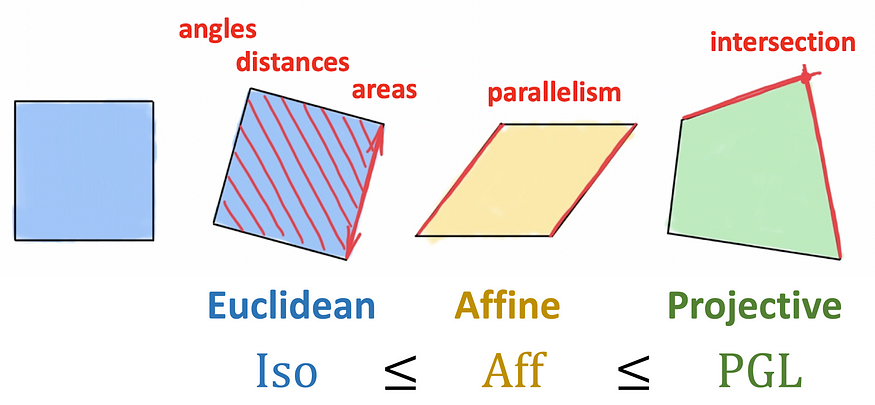

The breakthrough insight of Klein was to approach the definition of geometry as the study of invariants, or in other words, structures that are preserved under a certain type of transformations (symmetries). Klein used the formalism of group theory to define such transformations and use the hierarchy of groups and their subgroups in order to classify different geometries arising from them. Thus, the group of rigid motions leads to the traditional Euclidean geometry, while affine or projective transformations produce, respectively, the affine and projective geometries. Importantly, the Erlangen Program was limited to homogeneous spaces [2] and initially excluded Riemannian geometry.

Klein’s Erlangen Program approached geometry as the study of properties remaining invariant under certain types of transformations. 2D Euclidean geometry is defined by rigid transformations (modeled as the isometry group) that preserve areas, distances, and angles, and thus also parallelism. Affine transformations preserve parallelism, but neither distances nor areas. Finally, projective transformations have the weakest invariance, with only intersections and cross-ratios preserved, and correspond to the largest group among the three. Klein thus argued that projective geometry is the most general one.

The impact of the Erlangen Program on geometry and mathematics broadly was very profound. It also spilled to other fields, especially physics, where symmetry considerations allowed to derive conservation laws from the first principles — an astonishing result known as Noether’s Theorem [3]. It took several decades until this fundamental principle — through the notion of gauge invariance (in its generalized form developed by Yang and Mills in 1954) — proved successful in unifying all the fundamental forces of nature with the exception of gravity. This is what is called the Standard Model, and it describes all the physics we currently know. We can only repeat the words of a Nobel-winning physicist, Philip Anderson [4], that

“it is only slightly overstating the case to say that physics is the study of symmetry.’’

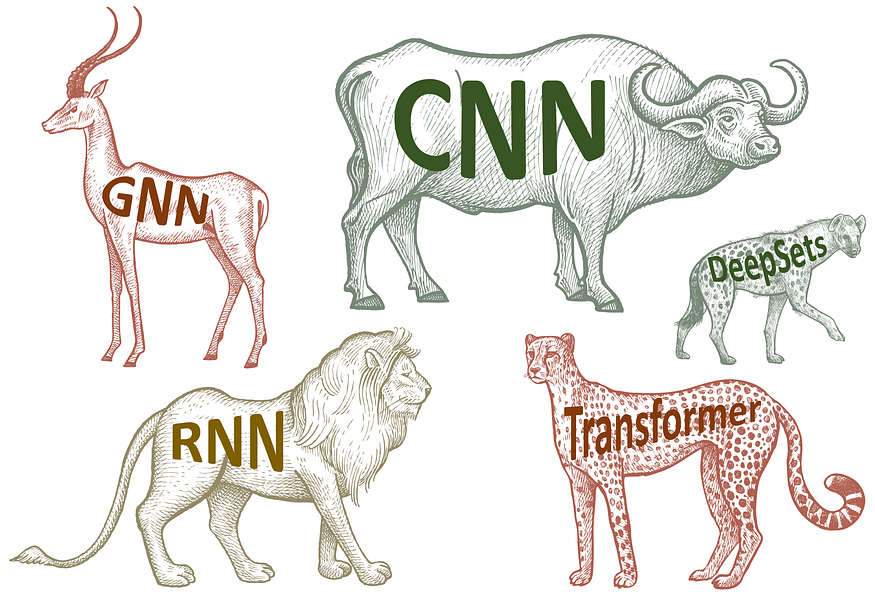

We believe that the current state of affairs in the field of deep (representation) learning is reminiscent of the situation of geometry in the nineteenth century: on the one hand, in the past decade, deep learning has brought a revolution in data science and made possible many tasks previously thought to be beyond reach — whether computer vision, speech recognition, natural language translation, or playing Go. On the other hand, we now have a zoo of different neural network architectures for different kinds of data but few unifying principles. As a consequence, it is difficult to understand the relations between different methods, which inevitably leads to the reinvention and re-branding of the same concepts.

Deep learning today: a zoo of architectures, few unifying principles. Animal images: ShutterStock.

Geometric Deep Learning is an umbrella term we introduced in [5] referring to recent attempts to come up with a geometric unification of ML similar to Klein’s Erlangen Program. It serves two purposes: first, to provide a common mathematical framework to derive the most successful neural network architectures, and second, to give a constructive procedure to build future architectures in a principled way.

Supervised machine learning in its simplest setting is essentially a function estimation problem: given the outputs of some unknown function on a training set (e.g., labelled dog and cat images), one tries to find a function f from some hypothesis class that fits well the training data and allows to predict the outputs on previously unseen inputs. In the past decade, the availability of large, high-quality datasets such as ImageNet coincided with growing computational resources (GPUs), allowing the design of rich function classes that have the capacity to interpolate such large datasets.

Neural networks appear to be a suitable choice to represent functions because even the simplest architecture, like the Perceptron, can produce a dense class of functions when using just two layers, allowing to approximate any continuous function to any desired accuracy — a property known as Universal Approximation [6].

Multi-layer Perceptrons are universal approximators: with just one hidden layer, they can represent combinations of step functions, allowing to approximate any continuous function with arbitrary precision.

The setting of this problem in low-dimensions is a classical problem in approximation theory that has been studied extensively, with precise mathematical control of estimation errors. But the situation is entirely different in high dimensions: one can quickly see that in order to approximate even a simple class of, e.g., Lipschitz continuous functions, the number of samples grows exponentially with the dimension — a phenomenon known colloquially as the “curse of dimensionality.” Since modern machine learning methods need to operate with data in thousands or even millions of dimensions, the curse of dimensionality is always there behind the scenes making such a naive approach to learning impossible.

Illustration of the curse of dimensionality: in order to approximate a Lipschitz-continuous function composed of Gaussian kernels placed in the quadrants of a d-dimensional unit hypercube (blue) with error ε, one requires ????(1/εᵈ) samples (red points).

This is perhaps best seen in computer vision problems like image classification. Even tiny images tend to be very high-dimensional, but intuitively they have a lot of structure that is broken and thrown away when one parses the image into a vector to feed it into the Perceptron. If the image is now shifted by just one pixel, the vectorized input will be very different, and the neural network will need to be shown a lot of examples in order to learn that shifted inputs must be classified in the same way [7].

Fortunately, in many cases of high-dimensional ML problems, we have an additional structure that comes from the geometry of the input signal. We call this structure a “symmetry prior,” and it is a powerful general principle that gives us optimism in dimensionality-cursed problems. In our example of image classification, the input image x is not just a d-dimensional vector but a signal defined on some domain Ω, which in this case is a two-dimensional grid. The structure of the domain is captured by a symmetry group ???? — the group of 2D translations in our example — which acts on the points on the domain. In the space of signals ????(Ω), the group actions (elements of the group, ????∈????) on the underlying domain are manifested through what is called the group representation ρ(????) — in our case, it is simply the shift operator, a d×d matrix that acts on a d-dimensional vector [8].

Illustration of geometric priors: the input signal (image x∈????(Ω)) is defined on the domain (grid Ω), whose symmetry (translation group ????) acts in the signal space through the group representation ρ(????) (shift operator). Making an assumption on how the functions f (e.g., image classifier) interacts with the group restricts the hypothesis class.

The geometric structure of the domain underlying the input signal imposes structure on the class of functions f that we are trying to learn. One can have invariant functions that are unaffected by the action of the group, i.e., f(ρ(????)x)=f(x) for any ????∈???? and x. On the other hand, one may have a case where the function has the same input and output structure and is transformed in the same way as the input—such functions are called equivariant and satisfy f(ρ(????)x)=ρ(????)f(x) [9]. In the realm of computer vision, image classification is a good illustration of a setting where one would desire an invariant function (e.g., no matter where a cat is located in the image, we still want to classify it as a cat), while image segmentation, where the output is a pixel-wise label mask, is an example of an equivariant function (the segmentation mask should follow the transformation of the input image).

Another powerful geometric prior is “scale separation.” In some cases, we can construct a multiscale hierarchy of domains (Ω and Ω’ in the figure below) by “assimilating” nearby points and also producing a hierarchy of signal spaces that are related by a coarse-graining operator P. On these coarse scales, we can apply coarse-scale functions. We say that a function f is locally stable if it can be approximated as the composition of the coarse-graining operator P and the coarse-scale function, f≈f’∘P. While f might depend on long-range dependencies, if it is locally stable, these can be separated into local interactions that are then propagated towards the coarse scales [10].

Illustration of scale separation where we can approximate a fine-level function f as the composition f≈f’∘Pof a coarse-level function f’ and a coarse-graining operator P.

These two principles give us a very general blueprint of Geometric Deep Learning that can be recognized in the majority of popular deep neural architectures used for representation learning: a typical design consists of a sequence of equivariant layers (e.g., convolutional layers in CNNs), possibly followed by an invariant global pooling layer aggregating everything into a single output. In some cases, it is also possible to create a hierarchy of domains by some coarsening procedure that takes the form of local pooling.

Geometric Deep Learning blueprint.

This is a very general design that can be applied to different types of geometric structures, such as grids, homogeneous spaces with global transformation groups, graphs (and sets, as a particular case), and manifolds, where we have global isometry invariance and local gauge symmetries. The implementation of these principles leads to some of the most popular architectures that exist today in deep learning: Convolutional Networks (CNNs), emerging from translational symmetry, Graph Neural Networks, DeepSets [11], and Transformers [12], implementing permutation invariance, gated RNNs (such as LSTM networks) that are invariant to time warping [13], and Intrinsic Mesh CNNs [14] used in computer graphics and vision, that can be derived from gauge symmetry.

The “5G” of Geometric Deep Learning: Grids, Group (homogeneous spaces with global symmetries), Graphs (and sets as a particular case), and Manifolds, where geometric priors are manifested through global isometry invariance (which can be expressed using Geodesics) and local Gauge symmetries.

In future posts, we will be exploring in further detail the instances of the Geometric Deep Learning blueprint on the “5G” [15]. As a final note, we should emphasize that symmetry has historically been a key concept in many fields of science, of which physics, as already mentioned in the beginning, is key. In the machine learning community, the importance of symmetry has long been recognized in particular in the applications to pattern recognition and computer vision, with early works on equivariant feature detection dating back to Shun’ichi Amari [16] and Reiner Lenz [17]. In the neural networks literature, the Group Invariance Theorem for Perceptrons by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert [18] put fundamental limitations on the capabilities of (single-layer) Perceptrons to learn invariants. This was one of the primary motivations for studying multi-layer architectures [19–20], which had ultimately led to deep learning.

Footnotes and References

[1] According to a popular belief, repeated in many sources, including Wikipedia, the Erlangen Program was delivered in Klein’s inaugural address in October 1872. Klein indeed gave such a talk (though on December 7, 1872), but it was for a non-mathematical audience and concerned primarily with his ideas of mathematical education. What is now called the “Erlangen Programme” was actually the aforementioned brochure Vergleichende Betrachtungen, subtitled Programm zum Eintritt in die philosophische Fakultät und den Senat der k. Friedrich-Alexanders-Universität zu Erlangen (“Program for entry into the Philosophical Faculty and the Senate of the Emperor Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen,” see an English translation). While Erlangen claims the credit, Klein stayed there for only three years, moving in 1875 to the Technical University of Munich (then called Technische Hochschule), followed by Leipzig (1880), and finally settling down in Göttingen from 1886 until his retirement. See R. Tobies Felix Klein — Mathematician, Academic Organizer, Educational Reformer (2019) In: H. G. Weigand et al. (eds) The Legacy of Felix Klein, Springer.

[2] A homogeneous space is a space where “all points are the same,” and any point can be transformed into another by means of group action. This is the case for all geometries proposed before Riemann, including Euclidean, affine, and projective, as well as the first non-Euclidean geometries on spaces of constant curvature such as the sphere or hyperbolic space. It took substantial effort and nearly 50 years, notably by Élie Cartan and the French geometry school, to extend Klein’s ideas to manifolds.

[3] Klein himself has probably anticipated the potential of his ideas in physics, complaining of “how persistently the mathematical physicist disregards the advantages afforded him in many cases by only a moderate cultivation of the projective view.” By that time, it was already common to think of physical systems through the perspective of the calculus of variation, deriving the differential equations governing such systems from the “least action principle,” i.e., as the minimizer of some functional (action). In a paper published in 1918, Emmy Noether showed that every (differentiable) symmetry of the action of a physical system has a corresponding conservation law. This, by all means, was a stunning result: beforehand, meticulous experimental observation was required to discover fundamental laws such as the conservation of energy, and even then, it was an empirical result not coming from anywhere. For historical notes, see C. Quigg, Colloquium: A Century of Noether’s Theorem (2019), arXiv:1902.01989.

[4] P. W. Anderson, More is different (1972), Science 177(4047):393–396.

[5] M. M. Bronstein et al. Geometric deep learning: going beyond Euclidean data (2017), IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 34(4):18–42 attempted to unify learning on grids, graphs, and manifolds from the spectral analysis perspective. The term “geometric deep learning” was actually coined earlier, in Michael’s ERC grant proposal.

[6] There are multiple versions of the Universal Approximation theorem. It is usually credited to G. Cybenko, Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function (1989) Mathematics of Control, Signals, and Systems 2(4):303–314 and K. Hornik, Approximation capabilities of multi-layer feedforward networks (1991), Neural Networks 4(2):251–257.

[7] The remedy for this problem in computer vision came from classical works in neuroscience by Hubel and Wiesel, the winners of the Nobel prize in medicine for the study of the visual cortex. They showed that brain neurons are organized into local receptive fields, which served as an inspiration for a new class of neural architectures with local shared weights, first the Neocognitron in K. Fukushima, A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position (1980), Biological Cybernetics 36(4):193–202, and then the Convolutional Neural Networks, the seminar work of Y. LeCun et al., Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition (1998), Proc. IEEE 86(11):2278–2324, where weight sharing across the image effectively solved the curse of dimensionality.

[8] Note that a group is defined as an abstract object, without saying what the group elements are (e.g., transformations of some domain), only how they compose. Hence, very different kinds of objects may have the same symmetry group.

[9] These results can be generalized for the case of approximately invariant and equivariant functions, see e.g., J. Bruna and S. Mallat, Invariant scattering convolution networks (2013), Trans. PAMI 35(8):1872–1886.

[10] Scale separation is a powerful principle exploited in physics, e.g., in the Fast Multipole Method (FMM), a numerical technique originally developed to speed up the calculation of long-range forces in n-body problems. FMM groups sources that lie close together and treat them as a single source.

[11] M. Zaheer et al., Deep Sets (2017), NIPS. In the computer graphics community, a similar architecture was proposed in C. R. Qi et al., PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation (2017), CVPR.

[12] A. Vaswani et al., Attention is all you need (2017), NIPS, introduced the now popular Transformer architecture. It can be considered as a graph neural network with a complete graph.

[13] C. Tallec and Y. Ollivier, Can recurrent neural networks warp time? (2018), arXiv:1804.11188.

[14] J. Masci et al., Geodesic convolutional neural networks on Riemannian manifolds (2015), arXiv:1501.06297 was the first convolutional-like neural network architecture with filters applied in local coordinate charts on meshes. It is a particular case of T. Cohen et al., Gauge Equivariant Convolutional Networks and the Icosahedral CNN (2019), arXiv:1902.04615.

[15] M. M. Bronstein, J. Bruna, T. Cohen, and P. Veličković, Geometric Deep Learning: Grids, Groups, Graphs, Geodesics, and Gauges (2021)

[16] S.-l. Amari, Feature spaces which admit and detect invariant signal transformations (1978), Joint Conf. Pattern Recognition. Amari is also famous as the pioneer of the field of information geometry, which studies statistical manifolds of probability distributions using tools of differential geometry.

[17] R. Lenz, Group theoretical methods in image processing (1990), Springer.

[18] M. Minsky and S. A Papert. Perceptrons: An introduction to computational geometry (1987), MIT Press. This is the second edition of the (in)famous book blamed for the first “AI winter,” which includes additional results and responds to some of the criticisms of the earlier 1969 version.

[19] T. J. Sejnowski, P. K. Kienker, and G. E. Hinton, Learning symmetry groups with hidden units: Beyond the perceptron (1986), Physica D:Nonlinear Phenomena 22(1–3):260–275

[20] J. Shawe-Taylor, Building symmetries into feedforward networks (1989), ICANN. The first work that can be credited with taking a representation-theoretical view on invariant and equivariant neural networks is J. Wood and J. Shawe-Taylor, Representation theory and invariant neural networks (1996), Discrete Applied Mathematics 69(1–2):33–60. In the “modern era” of deep learning, building symmetries into neural networks was done by R. Gens and P. M. Domingos, Deep symmetry networks (2014), NIPS (see also Pedro Domingos’ invited talk at ICLR 2014)

We are grateful to Ben Chamberlain for proofreading this post and to Yoshua Bengio, Charles Blundell, Andreea Deac, Fabian Fuchs, Francesco di Giovanni, Marco Gori, Raia Hadsell, Will Hamilton, Maksym Korablyov, Christian Merkwirth, Razvan Pascanu, Bruno Ribeiro, Anna Scaife, Jürgen Schmidhuber, Marwin Segler, Corentin Tallec, Ngân Vu, Peter Wirnsberger, and David Wong for their feedback on different parts of the text on which this post is based. We also that Xiaowen Dong and Pietro Liò for helping us break the “stage fright” and present early versions of our work.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Bios: Michael Bronstein is Professor and Chair in Machine Learning and Pattern Recognition at Imperial College and the Head of Graph Learning Research at Twitter. Joan Bruna is an Associate Professor of Computer Science, Data Science and Mathematics at the Courant Institute and the Center for Data Science, New York University. Taco Cohen is a machine learning researcher at Qualcomm with a PhD in Machine Learning from the University of Amsterdam. Petar Veličković is a Senior Research Scientist at DeepMind with a PhD in Computer Science from the University of Cambridge (Trinity College).

Related:

Geometric foundations of Deep Learning

Geometric foundations of Deep Learning