Navigating AI Entrepreneurship: Insights From The Application Layer

Through the lens of a serial entrepreneur, this article explores how the AI revolution is shifting from infrastructure to the application layer, where the greatest opportunities lie in solving specialized, data-heavy industry problems rather than perfecting raw technology.

Image by Editor

# Introduction

The AI industry is experiencing a wave of transformation comparable to the dot-com era, and entrepreneurs are rushing to stake their claims in this emerging landscape. Yet unlike previous technology waves, this one presents a unique characteristic: the infrastructure is maturing faster than the market can absorb it. This gap between technological capability and practical implementation defines the current opportunity landscape.

Andrei Radulescu-Banu, founder of DocRouter AI and SigAgent AI, brings a unique perspective to this conversation. With a PhD in mathematics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and decades of engineering experience, Radulescu-Banu has built document processing platforms powered by large language models (LLMs) and developed monitoring systems for AI agents, all while serving as a fractional chief technology officer (CTO) helping startups implement AI solutions.

His journey from academic mathematician to hands-on engineer to AI entrepreneur was not straightforward. "I've done many things in my career, but one thing I've not done is actually entrepreneurship," he explains. "I just wish I had started this when I was, I don't know, out of college, actually." Now, he is making up for lost time with an ambitious goal of launching six startups in 12 months.

This accelerated timeline reflects a broader urgency in the AI entrepreneurship space. When technological shifts create new markets, early movers often capture disproportionate advantages. The challenge lies in moving quickly without falling into the trap of building technology in search of a problem.

# The Layering Of The AI Stack

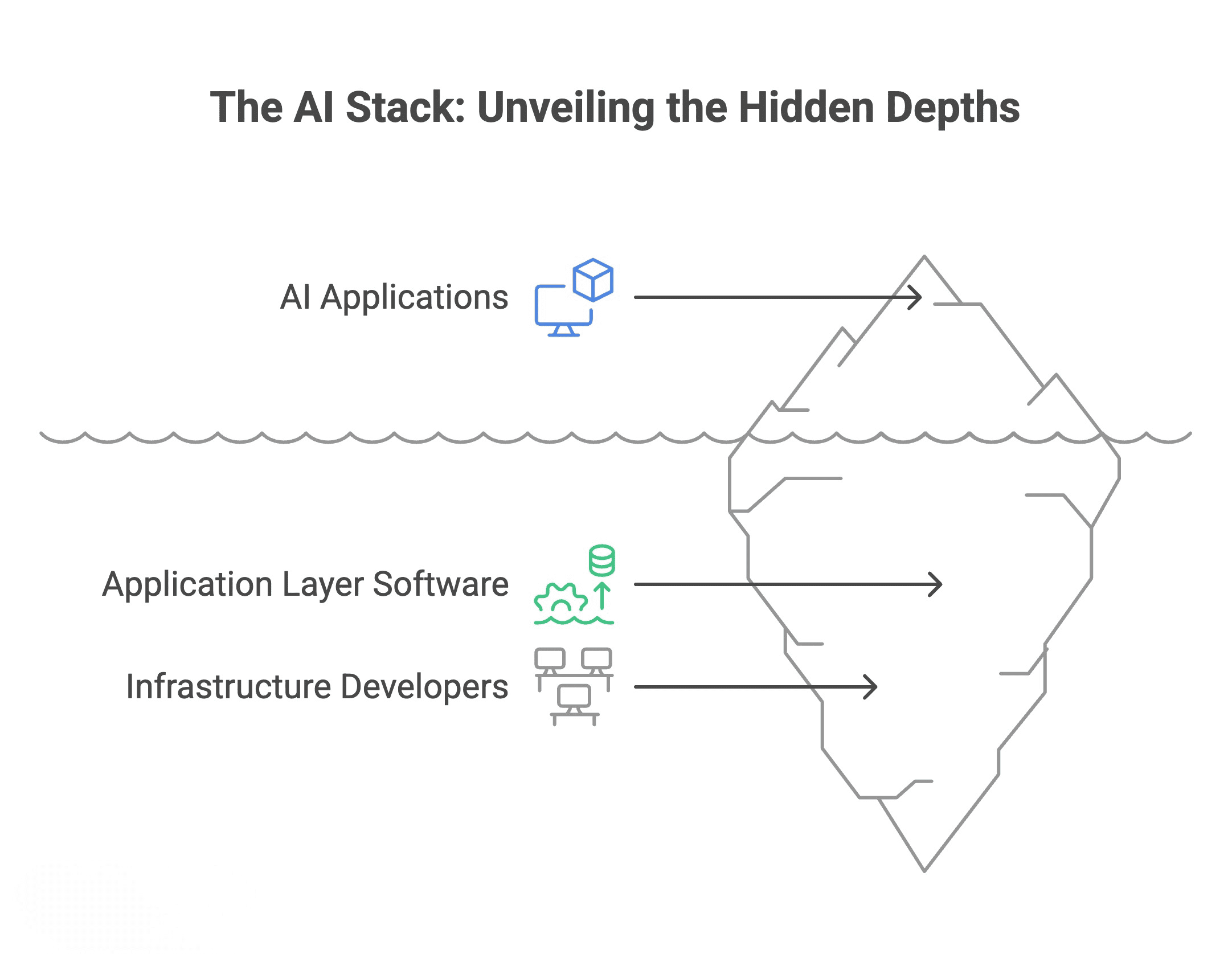

Radulescu-Banu draws parallels between today's AI boom and the internet revolution. "Just like in the past for computer networks, [you] had developers of infrastructure, let's say, computer switches and routers. And then you had application layer software sitting on top, and then you had web applications. So what's interesting is that these layers are forming now for the AI stack."

The emerging AI stack | Image by Editor

This stratification matters because different layers follow different economic models and face different competitive dynamics. Infrastructure providers engage in capital-intensive competition, racing to build data centers and secure GPUs. They must serve everyone, which means building increasingly generic solutions.

At the foundation layer, companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google compete intensely, driving prices down and commoditizing access to language models. "Companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, they're almost forced to compete with each other and they cannot specialize to one vertical," Radulescu-Banu observes. "They have to develop these generic language models that can solve any problem in the world."

The dynamics at the application layer differ fundamentally. Here, specialization becomes an advantage rather than a limitation. Deep understanding of specific industries, workflows, and pain points matters more than raw computational power.

The real opportunity, he argues, lies in the application layer. "Companies that layer on top, the wave is just beginning for that. So I'm referring here to this agentic layer, or things like vertical applications that are specific to legal or to medical or to something some other industry insurance or accounting." He sees this layer as unsaturated, with room for significant growth over the next five years.

This timeline aligns with historical patterns. During the dot-com era, infrastructure competition consolidated quickly while application-layer innovation continued for years. The same pattern appears to be emerging in AI, creating a longer runway for entrepreneurs focused on solving specific industry problems.

# From Medical Records To Platform

DocRouter AI emerged from consulting work in an unexpected vertical: durable medical equipment. Radulescu-Banu spent a year and a half helping a startup process medical records for oxygen tanks, wheelchairs, and CPAP masks. "All this process, all this coordination is very paper heavy. And it's an ideal ground for language models to process," he notes.

The durable medical equipment sector illustrates how AI opportunities often hide in unglamorous corners of the economy. These are not the attractive consumer applications that dominate headlines, but they represent substantial markets with real pain points and customers willing to pay for solutions.

The insight was recognizing that the same problem appears across industries. "The same problem repeats itself in many other industries, like for example, the legal. And legal itself has many subsegments, like say you're a law firm and you need to review, I don't know, thousands of documents to discover one tiny detail that is important for your case."

This pattern recognition represents a crucial entrepreneurial skill: seeing the abstract problem beneath specific implementations. Document-heavy coordination challenges plague legal discovery, patent research, insurance claims processing, and countless other workflows. Each vertical believes its problems are unique, but often they are variations on common themes.

His approach illustrates a broader strategy: build reusable technology. "The idea of DocRouter was to kind of take what worked for one segment of the industry and develop a platform that actually sits underneath and solves all the same problem in other verticals."

# The Technical Founder Paradox

One might assume technical expertise provides an advantage in building AI startups. Radulescu-Banu's experience suggests otherwise. "It might even be easier if you're not overly technical," he says. "Starting a company in a certain vertical, it's more important to know your customers and to have an understanding of where you want to take the product, than understanding how to build a product. The product can almost build itself."

This observation challenges assumptions many technically minded people hold about entrepreneurship. The ability to architect elegant solutions or optimize algorithms does not necessarily translate to identifying market opportunities or understanding customer workflows. In fact, deep technical knowledge can become a liability when it leads to over-engineering or building features customers do not value.

He points to the Boston robotics sector as an example. "There's a bunch of startups that come out of MIT that do robotics. And actually, many of them struggle quite a bit. Why? Because they're started by data scientists and by engineers." Meanwhile, Locus Robotics, started by salespeople who understood warehouse operations, "was a lot more successful than the companies that were started by engineers."

The Locus story reveals something important about vertical markets. The salespeople who founded it had spent years integrating robotics products from other companies into warehouses. They understood the operational constraints, procurement processes, and actual pain points that warehouse managers faced. Technical excellence mattered, but it was procured rather than developed in-house initially.

This does not mean technical founders cannot succeed. "Google was started by engineers. And Google was started by PhDs, actually," he acknowledges. "There isn't a hard and fast rule, but I think from my perspective, it's almost better to not be an engineer when you start a company."

The distinction may lie in the type of problem being solved. Google succeeded by solving a technical problem (search quality) that was universally recognized. Vertical AI applications often require solving business process problems where the technical solution is just one component.

For Radulescu-Banu, this has meant a personal shift. "What I'm learning now is this ability to kind of let some of the technical things go and not be overly focused on the technical things and learn to rely on other people to do the technical aspect." The temptation to perfect the architecture, optimize the code, or explore interesting technical tangents remains strong for many technical founders, making the transition more difficult. But entrepreneurship demands focusing energy where it creates the most value, which often means customer conversations rather than code optimization.

# Blurring The Consulting-Product Boundary

Entrepreneurs face persistent pressure to categorize themselves. "When you start a discussion about entrepreneurship, the first thing you're told is, are you a product or are you just doing consulting?" Radulescu-Banu explains. Investors prefer products because consulting companies "grow linearly" while products have "the potential to explode."

However, he has discovered a middle path. "Actually there isn't kind of a straight boundary between consulting and product. You can make it fuzzy and you can play both sides." His philosophy centers on efficiency: "I'm an advocate of never wasting work. So whenever I do something, I want to be sure that I'm going to use it two, three times."

DocRouter AI exists as both a product and a consulting tool. SigAgent AI, his agent monitoring platform, shares infrastructure with DocRouter. "Sigagent is basically 90% the same as DocRouter, but the infrastructure is the same, the database is the same. The technology is the same, but what's different is the application layer." This approach allows consulting to bootstrap product development while building reusable platforms that serve multiple purposes.

# The Maturation Of AI Reliability

The technical landscape has shifted dramatically in just one year. "If you roll the clock back maybe one year, language models were not working that well. You know, they had hallucinations," Radulescu-Banu recalls. "What happened in the past year is that the language models have evolved to be a lot more precise and to hallucinate a lot less."

This rapid improvement has significant implications for production AI systems. Problems that seemed intractable or risky twelve months ago now have, by comparison, more reliable solutions. The pace of progress means that companies postponing AI adoption due to reliability concerns may find themselves increasingly behind competitors who moved earlier.

The challenge has evolved. "If you give the right context to a language model, you can be pretty certain that you're going to get the right result. So that part has been de-risked, and now it's become a context engineering problem. But that doesn't make it any easier because it's actually very complicated to give the language model exactly the piece that it needs to solve the problem. Nothing more, nothing less."

Context engineering represents a new category of technical challenge. It combines elements of information architecture, prompt engineering, and system design. Success requires understanding both the domain (what information matters) and the model's capabilities (how to structure that information for optimal results). This emerging discipline will likely become a specialized skill set as AI applications mature.

Regulatory concerns, often cited as barriers to AI adoption, are primarily procedural rather than technical. For healthcare, "you kind of deal with it with process. You make sure you have the right process in place, you have the right auditors in place. You follow the rules, and it can all be done." These frameworks, he suggests, can actually guide companies toward building systems correctly.

The regulatory landscape, while complex, offers structure rather than reassurance. Frameworks such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), System and Organization Controls (SOC) 2, Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), and financial regulations enforced by bodies like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) impose clear requirements, but they also highlight how poorly suited many AI systems are for high-risk, regulated environments. Building toward these standards from the outset is costly and constraining, and retrofitting compliance later is often even more difficult, particularly as models evolve in opaque ways.

# The Adoption Gap

Despite technological readiness, industries lag in implementation. "We've got all these wonderful technology that is available, but the industry is not quick enough to absorb and implement everything that is possible," Radulescu-Banu observes.

The problem manifests as both a skills shortage and a trust deficit. "I think what is missing is people don't trust agents and don't trust that they can solve problems with agents. And the technology has evolved and it's ready to do it." He sees this repeatedly in consulting: "You join companies that need this work and in this company, you see two or three engineers that are ready to do this and they're learning how to do this. But the company has 50, 100 engineers."

This skill distribution reflects how new technologies diffuse through organizations. Early adopters experiment and build expertise, but scaling requires broader organizational capability. Companies face a chicken-and-egg problem: they cannot fully commit to AI transformation without skilled teams, but building those skills requires hands-on experience with real projects.

Modern development tools like Cursor, Claude Code, and GitHub Copilot are available, but adoption faces resistance. "Some companies are worried and they would say, but now AI is going to see all this source code, what are we going to do? Well, guess what? Now AI can rewrite all the source code pretty much in a couple of nights with the right engineering."

# Learning Entrepreneurship

Without co-founders or entrepreneurial colleagues, Radulescu-Banu had to find alternative learning paths. "When you're an entrepreneur, you don't have other colleagues who are entrepreneurs who work with you. So how do you meet these people? Well, so it turns out what you do is you go to these meetups and you, again, look over their shoulder and ask questions."

This learning path differs fundamentally from how most professionals develop expertise. In traditional employment, learning happens organically through daily interaction with colleagues. Entrepreneurship requires more deliberate networking and knowledge-seeking. The meetup circuit becomes a substitute workplace for exchanging ideas and learning from others' experiences.

The entrepreneurial community proved surprisingly supportive. "Usually entrepreneurs are very open about what they do, and they like to help other entrepreneurs. That's an interesting thing that they're very supportive of each other." This allowed him to learn entrepreneurship "on the job also just like I learned engineering. It's just that you don't learn it doing your work, but you learn it by meeting people and asking them how they do it."

This openness contrasts with the competitive dynamics one might expect. Perhaps entrepreneurs recognize that success depends more on execution than on secret knowledge. Or perhaps the act of explaining one's approach to others helps clarify thinking and identify blind spots. Whatever the mechanism, this knowledge-sharing culture accelerates learning for newcomers willing to engage with the community.

# Regional Dynamics

Boston presents a puzzle for AI entrepreneurs. The city boasts world-class universities and exceptional talent, yet something does not quite click. "Boston is peculiar in that it's got these great colleges and it's got these people with great skills, but somehow, the investment machinery doesn't work the same as in, let's say, San Francisco or New York City."

This observation points to subtle but important differences in startup ecosystems. Boston produces exceptional technical talent and has strong academic institutions, but the venture capital culture, risk tolerance, and network effects differ from Silicon Valley. These differences affect everything from fundraising to talent recruitment to exit opportunities.

Understanding these regional differences matters for anyone building a startup outside Silicon Valley. The challenges are real, but so are the opportunities for those who can navigate the local ecosystem effectively. Boston's strengths in biotech, robotics, and enterprise software suggest that certain types of AI applications may find more natural traction than others.

Some of the gap may reflect different definitions of success. Silicon Valley venture capital optimizes for massive exits and tolerates high failure rates. Boston's investment community, shaped partly by the region's biotech industry, may favor different risk-reward profiles. Neither approach is inherently superior, but understanding these cultural differences helps entrepreneurs set appropriate expectations and strategies.

// The Mindset Shift

Perhaps the most significant transformation in Radulescu-Banu's journey involves how he thinks about risk and opportunity. Reflecting on his years as an employee, he recalls a restrictive mindset: "I was very loath to get side gigs. Maybe that was the biggest mistake when I was an engineer. I was thinking, oh, my God, I'm working at this place, that means I'm almost obligated to every moment of my life, even at night, at 8, 9, 10 p.m., to not contribute to anything else."

This mindset reflects a sense of loyalty or obligation to employers, combined with fear of conflicts of interest, which prevents exploration of side projects or entrepreneurial experiments. Yet many employment agreements permit side work that does not compete directly or use company resources.

Entrepreneurship has changed that. "I've started doing risk differently than before. I would not think of kind of pushing the envelope in a certain way, in terms of product ideas, or in terms of saying, why don't we just do things completely different and go after this other thing?"

He has observed this pattern in successful entrepreneurs. "I've seen other very successful people who have this mentality that they're a bit of a hustler, in a good sense, in a sense that, you know, try this, try that, you know, if the door is closed, get through the window."

The hustler mentality intends to reflect resourcefulness, persistence, and willingness to try unconventional approaches. When traditional paths are blocked, entrepreneurs find alternatives rather than accepting defeat. This quality of adaptability can be influential in emerging markets where established playbooks do not exist yet.

# Looking Ahead

The opportunity in AI applications remains substantial, but timing matters. "This wave of AI coming is very interesting. We are at the beginning of the wave," Radulescu-Banu notes. The rush to build AI companies mirrors the dot-com era, complete with the risk of a bubble. But unlike the dot-com crash, "we're still going to be growing" in the application layer for years to come.

Historical parallels provide both encouragement and caution. The dot-com bubble produced lasting companies like Amazon, Google, and eBay alongside countless failures. The key distinction lay in solving real problems with sustainable business models rather than simply riding hype. The same pattern may repeat with AI, rewarding companies that create genuine value and less so for others.

For aspiring AI entrepreneurs, his message is clear: the technology is ready, the market is forming, and the adoption gap represents opportunity rather than obstacle. The challenge lies in balancing technical capability with market understanding, building efficiently through reusable platforms, and moving quickly while industries are still learning what AI can do.

"I think that's where the opportunity is," he concludes, speaking of the agentic application layer. For those willing to navigate the complexity of consulting-product hybrids, regulatory requirements, and regional investment ecosystems, the next five years promise significant growth.

For those with the right combination of technical understanding, market insight, and willingness to learn, the current moment offers opportunities that may not persist once industries fully absorb what is already possible. For them, the question is not whether to participate in the AI wave, but how quickly entrepreneurs can position themselves to ride it effectively.

Rachel Kuznetsov has a Master's in Business Analytics and thrives on tackling complex data puzzles and searching for fresh challenges to take on. She's committed to making intricate data science concepts easier to understand and is exploring the various ways AI makes an impact on our lives. On her continuous quest to learn and grow, she documents her journey so others can learn alongside her. You can find her on LinkedIn.