The brain as a neural network: this is why we can’t get along

This article sets out to answer the question: what insights can we gain about ourselves by thinking of the brain as a machine learning model?

A few months ago, I was having a conversation with my co-workers, and noticed something a little strange that’s since changed the way I think about politics, and my own mind.

The topic of the day was introspection and politics. We were asking each other questions like, “What do you think your blind spots are as a libertarian?”, and “What about yours, as a feminist?” I lost track of time — as I usually do in these situations — and before I knew it, it was well past 1:00AM, and it felt like we were only starting to peel back the first few layers of the world’s problems.

The strange thing about our conversation wasn’t the topic itself. I love intense philosophical conversations that go nowhere and everywhere, and I probably have more of them than I should. No, what was strange was the language we were using to discuss the topic.

Because each of us had a background in machine learning, we shared a common vocabulary — one that includes technical terms like “decision surface” and “overfitting”. And as we explored our biases and opinions more deeply through the evening, it became clear that this unusual vocabulary was allowing us to gain remarkably powerful insights into our own thought processes.

In some ways, that actually makes a lot of sense: the most successful machine learning algorithms are neural networks, and their structure and function was explicitly inspired by that of the brain. So it shouldn’t be surprising that the vocabulary of machine learning should be unusually well-suited to providing insights into how we think, or fail at thinking, about the world’s problems.

I want to share one of those insights with you here. There are many others, but you probably have other things to do, and I really need to finish this post before midnight if I’m going to catch my train tomorrow morning.

Our brain as a neural network

Let’s think of our brains as a collection of neural networks. We’ll imagine that each of these networks is responsible for making (at least) one type of prediction.

Now let’s also imagine that there’s a city election, and that we need to choose which candidate we’re going to support for Mayor. According to the model we’re using, there’s going to be a neural network responsible for making decisions about politics.

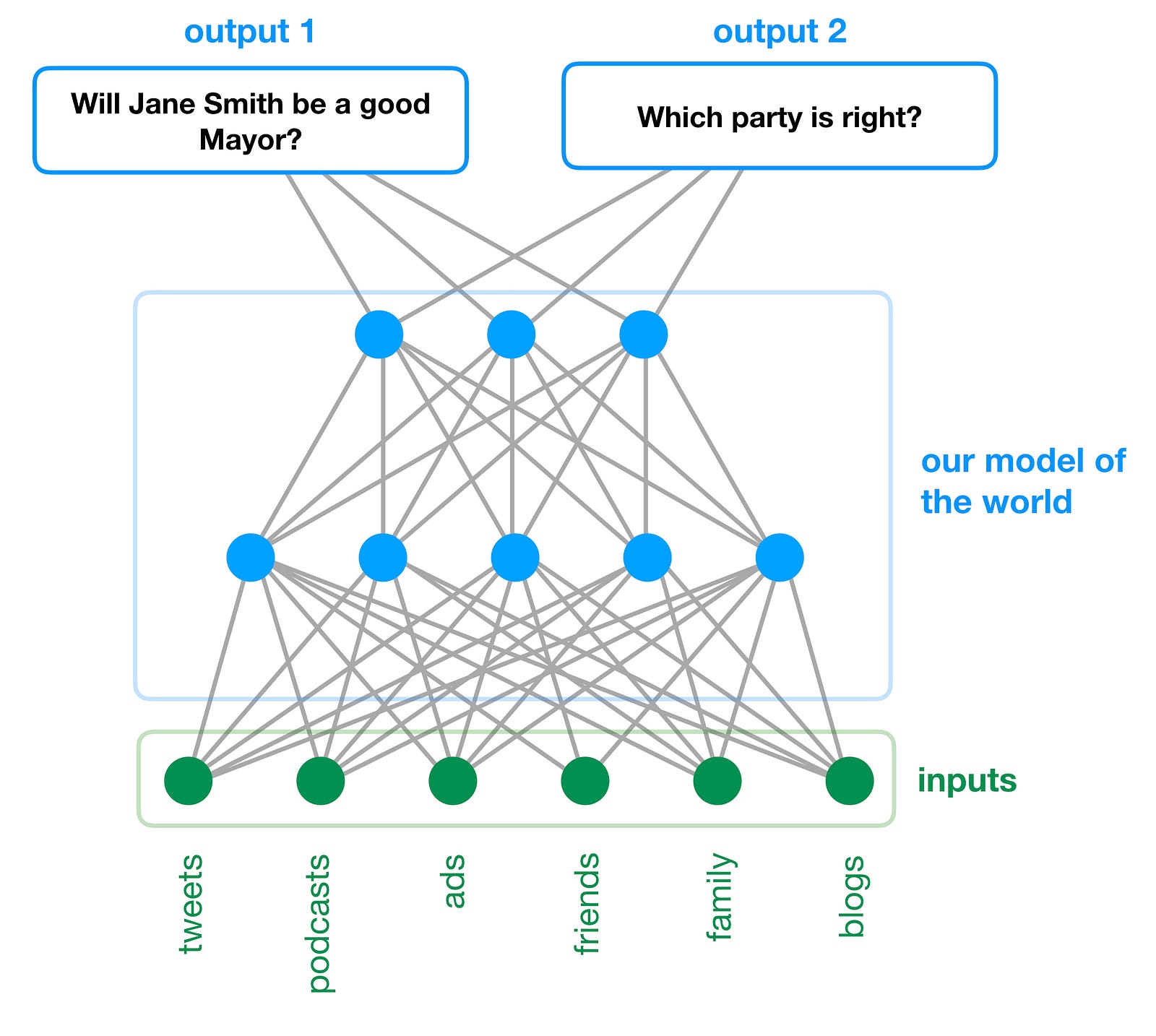

That neural network is going to take in a variety of inputs: our friends’ opinions, any tweets we’ve seen, campaign ads we’ve watched, podcasts we’ve listened to, etc. And it’s going to give us our political opinions as its output: which party we think is the “good” one, which candidates we expect to perform best when they’re elected, how high our tax rates should be, etc., etc. Essentially, this neural network encodes our political “model of the world”.

For simplicity, let’s imagine that it only has two outputs: 1) whether or not our favourite candidate (we’ll call her Jane Smith) will do a good job if she’s elected Mayor, and 2) which political party is the “good” one.

Here’s a sketch of what that might look like:

*Aside: Notice that both of the outputs of this model are built on top of the same underlying model. This is an idealization that’s important in order to ensure the internal consistency of our worldview. If output 1 and output 2 were generated by completely independent neural networks, then we could hit points of blatant contradiction, where we apply different rules when making one kind of political prediction than when making another.

Let’s say that we’d predicted Jane Smith would do a great job, but it later turns out that our prediction was completely incorrect. If we were perfectly rational, our next move would be pretty simple: we’d back-propagate through our model, tweaking its weights so that next time we come across a candidate like Jane, we’ll be more skeptical.

But that backpropagation might have other consequences as well. Specifically, it might also affect the predictions we’d made about which party is right.

Now, a perfectly rational person might say, “so what? If I have to re-evaluate my party affiliation to accommodate the facts, then so be it.”

But humans aren’t rational. We’re profoundly tribal, and many of us identify with our politics very deeply. In many cases, social pressure and conditioning directly influence the loss function associated with output 2 (our party affiliation), and require that output 2 takes on a certain specific value.

For example, the statement “I’m a Republican” necessarily requires that the value of output 2 is “the Republican Party is right”. Likewise, “I’m a Democrat” is a commitment to ensuring that output 2 is always “the Democratic Party is right”.

It’s worth taking a moment to think about the consequences of this constraint. As we’ll see, we can learn a lot about the math behind irrational human behaviour by doing it.

Overfitting = stubbornness + reality

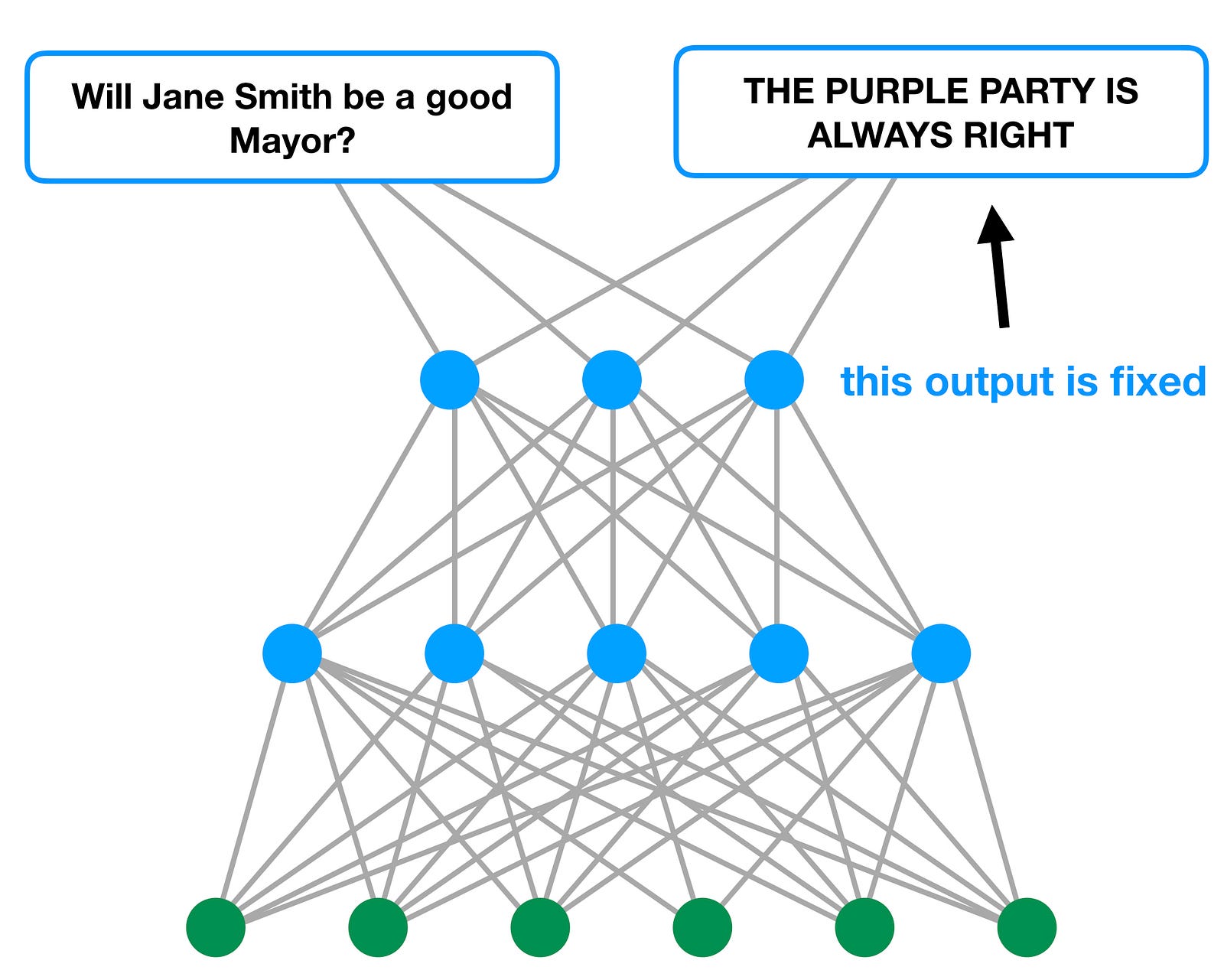

Let’s assume that Jane Smith was a member of our favourite political party. In the interest of neutrality, we’ll call it the Purple Party. Let’s also assume that we’re a partisan junkie, and there’s enough social and other pressure on us to support the Purple Party that we’re unwilling to budge on our party affiliation.

In that case, our response to Jane Smith’s performance in office is going to be a constrained optimization. On the one hand, we clearly have something to learn, since we supported Jane and it turned out that she wasn’t fit for the job after all. On the other, we can’t update our weights in such a way as to compromise our party preferences.

Here’s what this looks like, using our earlier picture:

Here’s the thing, though: depending on the state our model was in at the outset, it may be very difficult for us to update our weights in order to correctly predict Jane’s failure to perform as Mayor, without destroying our pro-Purple Party position in the process.

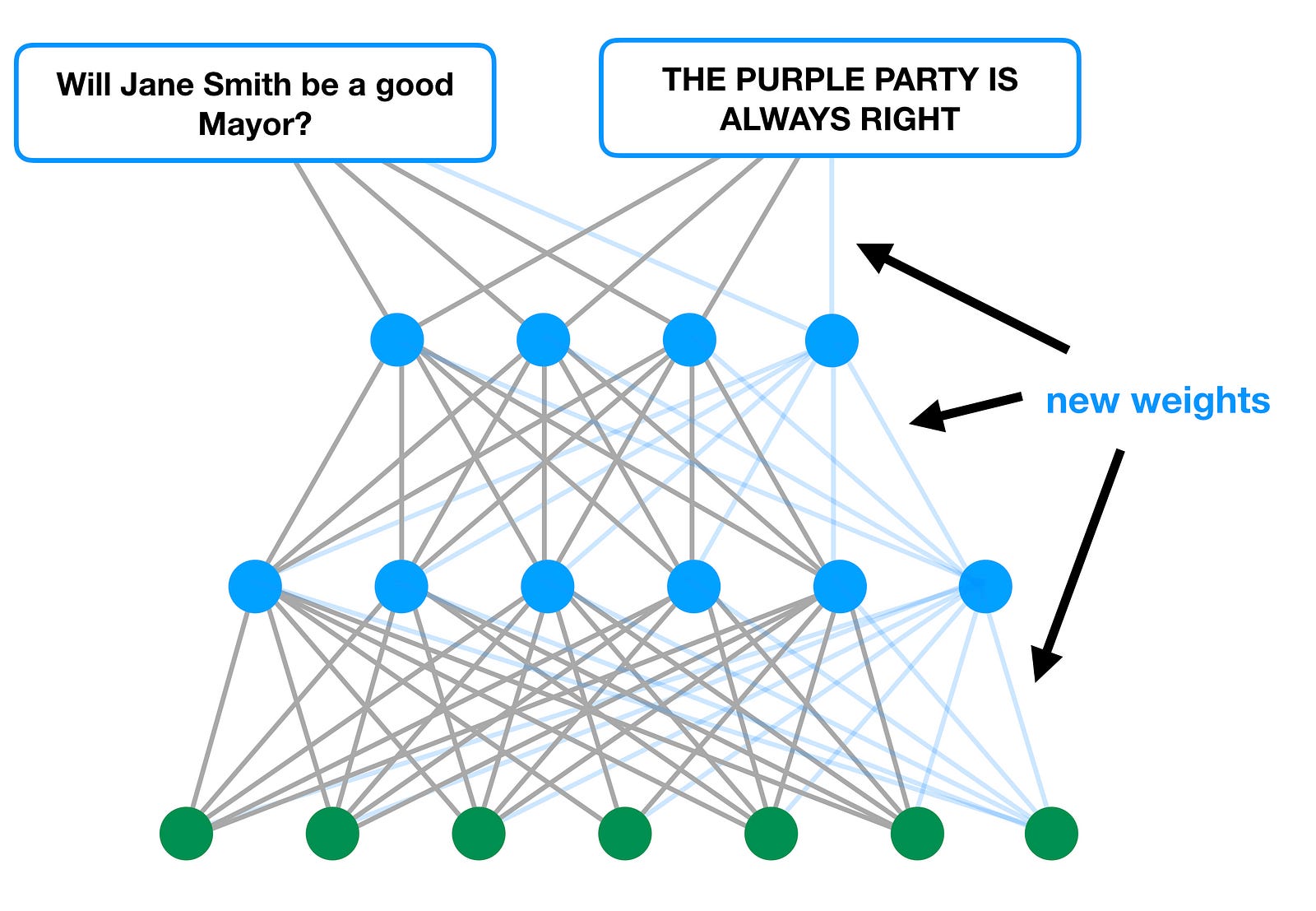

So what can we do if that happens? One option comes to mind: maybe all we need to do is add some degrees of freedom to our model, to get around this constraint!

And that, I’ll argue, is exactly what we do: rather than changing our party affiliation or our worldview, we simply add weights, and allow ourselves to preserve output 2 by overfitting:

Overfitting is the natural result of wanting to have our cake and eat it too: if we’re going to be stubborn and insist that the Purple Party is always right, but we also want to be able to justify their candidate’s bad performance, all we can do is give ourselves more degrees of freedom to work with.

What does overfitting feel like?

I’ve introduced overfitting very theoretically up to now. But it can be difficult to imagine how overfitting actually manifests itself in our thinking, so we should probably look at a concrete example.

Let’s go back to Jane and the terrible job she did as Mayor. If we’re going to overfit to this situation, we need to invent some new features (and maybe some new inputs) for our model, that allow us to explain how she failed without drawing the conclusion that the Purple Party needs to change its policies.

What might these features look like? In the ideal case, it will be something that we can manufacture, and yet which can’t be disproved or challenged. One great option that ticks all of these boxes is to go with is mind-reading: we can imagine the mental state of Jane Smith, and tune it until it gets us to the two conclusions that we want: 1) Jane Smith is a bad Mayor, and 2) the Purple Party is still great nonetheless. An easy way to do this is to say something like, “Sure, she was a Purple Party member, but Jane Smith never really believed in their platform. So you can’t judge the Purple Party based on her behavior.”

Fans of philosophy might recognize this as simply being an example of the No True Scotsman fallacy. As far as I can tell, the No True Scotsman fallacy is exactly what overfitting is. It’s a simple “yeah, but” response, designed to preserve our pre-existing biases without compromising our ability to explain reality by inventing new features as required. (“Yeah, but Jane isn’t a real Purple Party candidate, because [invented feature that allows overfitting].”)

By assuming that we have access to Jane Smith’s mental state, we’re able to pull the mind-reading lever at will, to ensure that we get the outcome we want from our model of the world, without sacrificing our ability to explain what we’ve observed of her candidacy. This strategy is great, because no one other than Jane Smith will ever be able to contradict us, and even if she does, we can always tell ourselves that “that’s exactly what she would say if she wasn’t being honest.”

A little introspection might reveal that we actually have an overfitting detector hard-wired into us. And that’s because overfitting is generally associated with a feeling: the feeling of making an excuse. After all, what is “an excuse” if not a new feature we’re introducing to our model of the world that allows us to explain our observations while preserving our dogma?

How to fight overfitting

If you want to be a more rational person, you might conclude that you need to confront overfitting head-on. And you might be tempted to think that you can tackle overfitting in your own mind the same way that you would in the context of a data science project: build a validation set, and check your predictions against it.

In practice, that might mean making predictions about the way that certain events will turn out, and holding your model of the world accountable for the accuracy of those predictions.

But this won’t always work, because it’s not uncommon to have to add features to your model of the world for perfectly legitimate reasons. In fact, to a great extent, that’s exactly what happens when we learn about a new problem, or a new field: we think about it in increasingly high dimensional terms, increasing all the while the complexity of our model.

So at the end of the day, your best bet might just be to pay close attention to your thought process, to try to catch yourself when you enter your excuse-making mode. Since that’s the telltale sign of overfitting, it’s your first indication that your model of the world might need just a little more tuning.

Bio: Jeremie Harris is the Co-founder of SharpestMinds (mentorship from senior data scientists that’s free until you get a job).

Original. Reposted with permission.

Resources:

- On-line and web-based: Analytics, Data Mining, Data Science, Machine Learning education

- Software for Analytics, Data Science, Data Mining, and Machine Learning

Related: