Order Matters: Alibaba’s Transformer-based Recommender System

Alibaba, the largest e-commerce platform in China, is a powerhouse not only when it comes to e-commerce, but also when it comes to recommender systems research. Their latest paper, Behaviour Sequence Transformer for E-commerce Recommendation in Alibaba, is yet another publication that pushes the state of the art in recommender systems.

By Serena McDonnell (Edited by Susan Shu & Omar Nada)

Another step towards Alibaba’s Recommender System Domination

Alibaba, the largest e-commerce platform in China, is a powerhouse not only when it comes to e-commerce, but also when it comes to recommender systems research. Their latest paper, Behaviour Sequence Transformer for E-commerce Recommendation in Alibaba, is yet another publication that pushes the state of the art in recommender systems. In this work, they make use of the popular Transformer model to capture sequential signals in user behaviour in online shopping, in order to perform next click prediction.

Ranking Candidates

Recommender systems often make use of a 2-stage paradigm of retrieval and ranking, and Alibaba’s approach is no different. The retrieval step used at Alibaba consists of selecting, with high recall, a subset of a million relevant candidate items from the entire item set (which is of course much larger than a million possible items), and the ranking step consists of ranking these candidates with high precision. This paper focuses on the ranking step, and specifically describes work revolving Alibaba’s Taobao, China’s largest Consumer-to-Consumer (C2C) platform.

The importance of sequential behaviour

When predicting the next click a user may make in online shopping, order matters. For example, a user will tend to click on a cellphone case after buying an iPhone, or they will try to find a pair of shoes to complement a pair of pants they have just bought. Previous work either completely ignores sequential signals of user behaviour (Cheng et. al, 2016), or encodes relationships between candidate items and previously clicked items without incorporating sequential nature of user’s clicks (Zhou et. al, 2017). The Transformer model, however, due to its use of self-attention, is able to capture dependency among items in a user’s behaviour sequence, and the importance of order. For this reason, the team at Alibaba and Taobao propose to leverage its power in their new model they call Behaviour Sequence Transformer (BST).

The BST Architecture

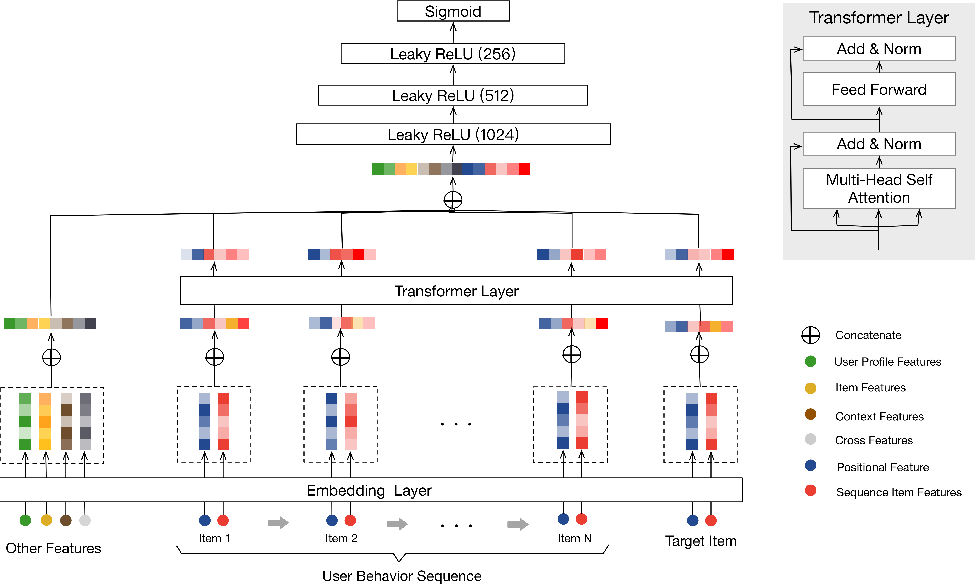

The recommendation task is modelled as a binary classification problem: given user u’s click behaviour sequence S(u) = {v1, v2, ..., vn}, where the user has clicked on n items, the task is to learn a function to predict the probability of user u clicking vt, a target candidate item at time t, given the previous items in the sequence. The BST model is an adaptation of Google's Wide & Deep Learning (WDL) model (Cheng et. al, 2016), where embeddings of previously clicked items and related features (category, price, etc) are concatenated and embedded into a low-dimensional vector, and then fed into a multi-layer perceptron. The BST architecture adds a Transformer layer to the WDL model, to better learn representations for users’ clicked items by capturing the sequential nature of those clicks.

The BST architecture is composed of several parts, described below, from the bottom up:

Embedding layer

In the first layer of the model, several types of features are embedded into low dimensional vectors, hence the name “embedding layer.” These features are 1) various item-level and user-level features, called “other features” (which are not gone into detail in the paper), 2) each item the user has clicked on, in sequence, called the “user behaviour sequence” and 3) the target candidate item. As a reminder, the candidate item comes from some candidate generation model, which this paper does not cover.

Every item in the behaviour click sequence is represented as the concatenation of 2 features:

- The “sequence item feature” which contains the

item_idandcategory_id. Note that although more item features exist, the authors found using these two worked best for performance. - The “positional feature,” which is used to capture order information in sequences, as the Transformer architecture alone has no notion of sequential order, unlike networks like RNNs. The positional value of item vi is expressed as pos(vi) = t(vt) - t(vi), where t(vt) represents the time of recommendation, and t(vi) is the time stamp at which the user clicked item vi. The authors found this to perform better than the sin and cos functions used in the original Transformer paper.

The user behaviour sequence and target item embeddings are then passed through the Transformer layer, while the “other features” are not.

Transformer layer

The transformer layer is itself made up of 2 sub-layers (see Figure 1) in which the embedding of each item in the user’s behaviour click sequence and the candidate item undergo several transformations. This results in embeddings for each item that incorporate their order and importance relative to the other items in the click sequence. We will go through each sub-layer one by one:

Self-attention sub-layer

The self-attention operation first takes the embeddings of items in the sequence as input, and for each item, creates a query, key, and value vector. These vectors are created for each item by multiplying its embedding by three projection matrices ,

,

that are learned during training, where d is the dimension of item embeddings. The queries, keys, and values for all items can be expressed as matrix form as

,

,

, where every row in the embedding matrix

corresponds to an item in the user's behaviour click sequence. Next, the

matrices are fed into a scaled-dot product attention layer to obtain an output, as defined below:

Performing the above operations once can be referred to as an attention “head”. As in the original Transformer paper, multi-head attention (MH) is used, where the attention operation is done multiple times for various randomly initialized projection matrices , and the results are concatenated, and multiplied by yet another weight matrix,

, as described below:

where h is the number of attention heads. The final result, , is passed to the next sub-layer in the Transformer.

Feed forward network sub-layer

As in the original Transformer paper, the output of the self-attention sub-layer is passed through a pointwise feed forward neural network.

Putting it all together

After each sub-layer, layer normalization, LeakyReLU, and dropout are applied. The overall output of the self-attention and FFN sub-layers together is as follows:

,

where and

are learnable parameters.

The result of the Transformer layer is a matrix , which represents the embeddings for items in a user's behaviour click sequence, and the target item, that incorporate the sequential nature of the user's clicks.

The MLP itself

The embeddings of the “other features” and output vectors from the Transformer layer are concatenated, and then passed through three fully connected layers, with ReLU activations, followed by a sigmoid activation, so that the probability that a user will click on the target item v_tvtcan be predicted. Cross-entropy loss is used for training:

where D represents all samples, is 1 if the user clicked the item and 0 otherwise, N is the number of training examples, and p(x) is the output of the BST network representing the probability of a user clicking on a candidate item x.

Experiments

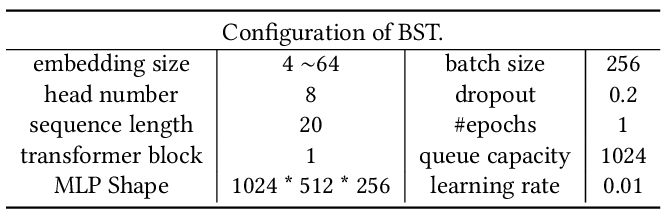

The BST model and baselines are implemented in Python 2.7 and Tensorflow 1.4, and “Adagrad” is chosen as the optimizer. Model parameters are shown in Table 1.

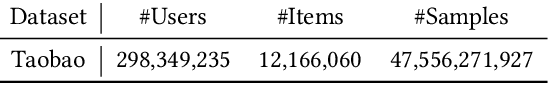

Experiments are done using 8 days of the transaction log from the Taobao App, where the first 7 days are used for training, and the last day is used for testing. The statistics of the dataset are shown in Table 2 below:

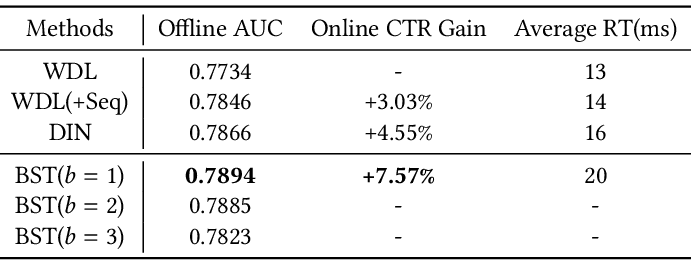

The baselines used are WDL and DIN, as well as WDL(+Seq) which is WDL with sequential information added, which includes averages of the embeddings of previously clicked items. To evaluate the performance of the models offline, AUC is used. An online A/B test is also done, with CTR and average response time (RT, the cost of generating recommendations for a given query) used to evaluate the models.

Results can be seen in Table 3. It’s clear, when comparing WDL to WDL(+Seq) in the offline experiment, that incorporating sequential information, even in a simple averaging manner, is important. It makes sense then that the BST model gives an improvement over the baselines, as can be seen by the results. The authors note that since the RT is close to that of WDL and DIN, this guarantees the feasibility of deploying a complex model like RT to production in a real-world, large-scale case.

Conclusion

The researchers at Alibaba have highlighted another case where ideas in NLP can be successfully applied to recommender systems. This paper makes two main contributions. First, it shows that by incorporating a Transformer layer into a standard multi-layer perceptron, BST is able to successfully capture sequential signals in user behaviour in online shopping, unlike previous models. Second, it shows that deploying BST in production at a large scale is not only feasible, but on par with current models in production at Alibaba and Taobao. It’ll be interesting to see what the recommender system research team at Alibaba does next.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- Building a Recommender System

- Building a Recommender System, Part 2

- Adapters: A Compact and Extensible Transfer Learning Method for NLP