Hands-On Reinforcement Learning Course, Part 1

Start your learning journey in Reinforcement Learning with this first of two part tutorial that covers the foundations of the technique with examples and Python code.

By Pau Labarta Bajo, mathematician and data scientist.

This first part covers the bare minimum concept and theory you need to embark on this journey from the fundamentals to cutting edge reinforcement learning (RL), step-by-step, with coding examples and tutorials in Python. In each following chapter, we will solve a different problem with increasing difficulty.

Ultimately, the most complex RL problems involve a mixture of reinforcement learning algorithms, optimization, and Deep Learning. You do not need to know deep learning (DL) to follow along with this course. I will give you enough context to get you familiar with DL philosophy and understand how it becomes a crucial ingredient in modern reinforcement learning.

In this first lesson, we will cover the fundamentals of reinforcement learning with examples, 0 maths, and a bit of Python.

1. What is a Reinforcement Learning problem?

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is an area of Machine Learning (ML) concerned with learning problems where

An intelligent agent needs to learn, through trial and error, how to take actions inside and environment in order to maximize a cumulative reward.

Reinforcement Learning is the kind of machine learning closest to how humans and animals learn.

What is an agent? And an environment? What are exactly these actions the agent can take? And the reward? Why do you say cumulative reward?

If you are asking yourself these questions, you are on the right track.

The definition I just gave introduces a bunch of terms that you might not be familiar with. In fact, they are ambiguous on purpose. This generality is what makes RL applicable to a wide range of seemingly different learning problems. This is the philosophy behind mathematical modeling, which stays at the roots of RL.

Let’s take a look at a few learning problems, and see how they use the RL lens.

Example 1: Learning to walk

As a father of a baby who recently started walking, I cannot stop asking myself, how did he learn that?

Kai and Pau.

As a Machine Learning engineer, I fantasize about understanding and replicating that incredible learning curve with software and hardware.

Let’s try to model this learning problem using the RL ingredients:

- The agent is my son, Kai. And he wants to stand up and walk. His muscles are strong enough at this point in time to have a chance at it. The learning problem for him is: how to sequentially adjust his body position, including several angles on his legs, waist, back, and arms to balance his body and not fall.

Sai hi to Kai!

- The environment is the physical world surrounding him, including the laws of physics. The most important of which is gravity. Without gravity, the learning-to-walk problem would drastically change and even become irrelevant: why would you want to walk in a world where you can simply fly? Another important law in this learning problem is Newton’s third law, which in plain words tells that if you fall on the floor, the floor is going to hit you back with the same strength. Ouch!

- The actions are all the updates in these body angles that determine his body position and speed as he starts chasing things around. Sure he can do other things at the same time, like imitating the sound of a cow, but these are probably not helping him accomplish his goal. We ignore these actions in our framework. Adding unnecessary actions does not change the modeling step, but it makes the problem harder to solve later on.An important (and obvious) remark is that Kai does not need to learn the physics of Newton to stand up and walk. He will learn through observing the state of the environment, taking action, and collecting feedback from this environment. He does not need to learn a model of the environment to achieve his goal.

- The reward he receives is a stimulus coming from the brain that makes him happy or makes him feel pain. There is the negative reward he experiences when falling on the floor, which is physical pain, maybe followed by frustration. On the other side, there are several things that contribute positively to his happiness, like the happiness of getting to places faster or the external stimulus that comes from my wife Jagoda and me when we say “good job!” or “bravo!” to each attempt and marginal improvement he shows.

A little bit more about rewards

The reward is a signal to Kai that what he has been doing is good or bad for his learning. As he takes new actions and experiences pain or happiness, he starts to adjust his behavior to collect more positive feedback and less negative feedback. In other words, he learns

Some actions might seem very appealing for the baby at the beginning, like trying to run to get a boost of excitement. However, he soon learns that in some (or most) cases, he ends up falling on his face and experiencing an extended period of pain and tears. This is why intelligent agents maximize cumulative reward and not marginal reward. They trade short-term rewards with long-term ones. An action that would give immediate reward, but put my body in a position about to fall, is not an optimal one.

Great happiness followed by greater pain is not a recipe for long-term well-being. This is something that babies often learn easier than we grown-ups.

The frequency and intensity of the rewards are key for helping the agent learn. Very infrequent (sparse) feedback means harder learning. Think about it, if you do not know if what you do is good or bad, how can you learn? This is one of the main reasons why some RL problems are harder than others.

Reward shaping is a tough modeling decision for many real-world RL problems.

Example 2: Learning to play Monopoly like a PRO

As a kid, I spent a lot of time playing Monopoly with friends and relatives. Well, who hasn’t? It is an exciting game that combines luck (you roll the dices) and strategy.

Monopoly is a real-estate board game for two to eight players. You roll two dices to move around the board, buying and trading properties, and developing them with houses and hotels. You collect rent from your opponents, with the goal being to drive them into bankruptcy.

Photo by Suzy Hazelwood from Pexels.

If you were so into this game that you wanted to find intelligent ways to play it, you could use some reinforcement learning.

What would the 4 RL ingredients be?

- The agent is you, the one who wants to win at Monopoly.

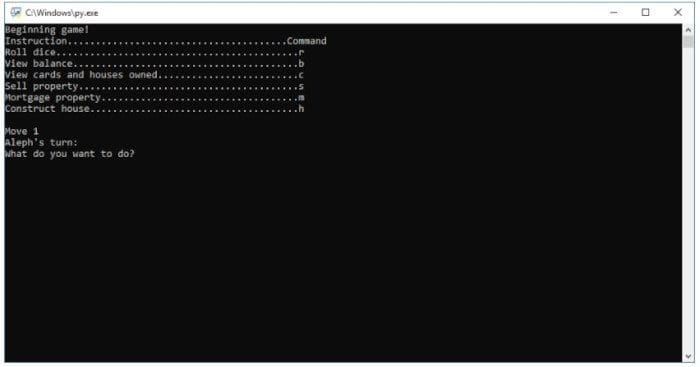

- Your actions are the ones you see on this screenshot below:

Action space in Monopoly. Credits to aleph aseffa.

- The environment is the current state of the game, including the list of properties, positions, and cash amount each player has. There is also the strategy of your opponent, which is something you cannot predict and lies outside of your control.

- And the reward is 0, except in your last move, where it is +1 if you win the game and -1 if you go bankrupt. This reward formulation makes sense but makes the problem hard to solve. As we said above, a more sparse reward means a harder solution. Because of this, there are other ways to model the reward, making them noisier but less sparse.

When you play against another person in Monopoly, you do not know how she or he will play. What you can do is play against yourself. As you learn to play better, your opponent does too (because it is you), forcing you to level up your game to keep on winning. You see the positive feedback loop.

This trick is called self-play. It gives us a path to bootstrap intelligence without using the external advice of an expert player. Self-play is the main difference between AlphaGo and AlphaGo Zero, the two models developed by DeepMind that play the game of Go better than any human.

Example 3: Learning to drive

In a matter of decades (maybe less), machines will drive our cars, trucks, and buses.

Photo by Ruiyang Zhang from Pexels.

But, how?

Learning to drive a car is not easy. The goal of the driver is clear: to get from point A to point B comfortably for her and any passengers on board.

There are many external aspects to the driver that make driving challenging, including:

- other drivers behavior

- traffic signs

- pedestrian behaviors

- pavement conditions

- weather conditions

- …even fuel optimization (who wants to spend extra on this?)

How would we approach this problem with reinforcement learning?

- The agent is the driver who wants to get from A to B comfortably.

- The state of the environment the driver observes has lots of things, including the position, speed, and acceleration of the car, all other cars, passengers, road conditions, or traffic signs. Transforming such a big vector of inputs into an appropriate action is challenging, as you can imagine.

- The actions are basically three: the direction of the steering wheel, throttle intensity, and break intensity.

- The reward after each action is a weighted sum of the different aspects you need to balance when driving. A decrease in distance to point B brings a positive reward, while an increase in a negative one. To ensure no collisions, getting too close (or even colliding) with another car or even a pedestrian should have a very big negative reward. Also, in order to encourage smooth driving, sharp changes in speed or direction contribute to a negative reward.

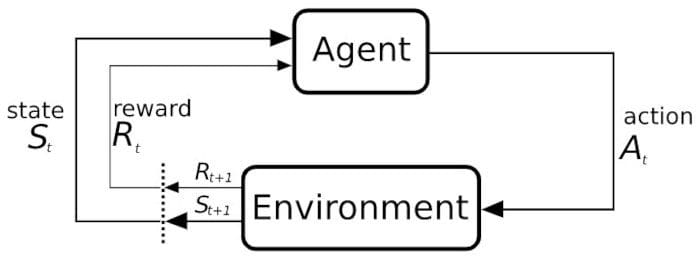

After these 3 examples, I hope the following representation of RL elements and how they play together makes sense:

RL in a nutshell. Credits to Wikipedia.

Now that we understand how to formulate an RL problem, we need to solve it.

But how?

2. Policies and value functions

Policies

The agent picks the action she thinks is the best based on the current state of the environment. This is the agent’s strategy, commonly referred to as the agent’s policy.

A policy is a learned mapping from states to actions.

Solving a reinforcement learning problem means finding the best possible policy.

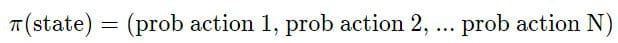

Policies are deterministic when they map each state to one action,

![]()

or stochastic when they map each state to a probability distribution over all possible actions.

Stochastic is a word you often read and hear in Machine Learning, and it essentially means uncertain or random. In environments with high uncertainty, like Monopoly where you are rolling dices, stochastic policies are better than deterministic ones.

There exist several methods to actually compute this optimal policy. These are called policy optimization methods.

Value functions

Sometimes, depending on the problem, instead of directly trying to find the optimal policy, one can try to find the value function associated with that optimal policy.

But, what is a value function? And before that, what does value mean in this context?

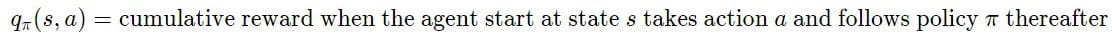

The value is a number associated with each state s of the environment that estimates how good it is for the agent to be in state s.

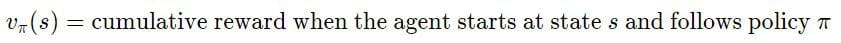

It is the cumulative reward the agent collects when starting at state s and choosing actions according to policy π.

A value function is a learned mapping from states to values.

The value function of a policy is commonly denoted as

Value functions can also map pairs of (action, state) to values. In this case, they are called q-value functions.

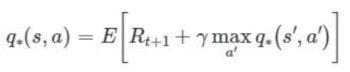

The optimal value function (or q-value function) satisfies a mathematical equation, called the Bellman equation.

This equation is useful because it can be transformed into an iterative procedure to find the optimal value function.

But, why are value functions useful?

Because you can infer an optimal policy from an optimal q-value function.

How?

The optimal policy is the one where at each state s the agent chooses the action a that maximizes the q-value function.

So, you can jump from optimal policies to optimal q-functions and vice versa.

There are several RL algorithms that focus on finding optimal q-value functions. These are called Q-learning methods.

The zoology of reinforcement learning algorithms

There are lots of different RL algorithms. Some try to directly find optimal policies, and others q-value functions, and others both at the same time.

The zoology of RL algorithms is diverse and a bit intimidating.

There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to RL algorithms. You need to experiment with a few of them each time you solve an RL problem and see what works for your case.

As you follow along this course, you will implement several of these algorithms and gain an insight into what works best in each situation.

3. How to generate training data?

Reinforcement learning agents are VERY data-hungry.

To solve RL problems, you need a lot of data.

A way to overcome this hurdle is by using simulated environments. Writing the engine that simulates the environment usually requires more work than solving the RL problem. Also, changes between different engine implementations can render comparisons between algorithms meaningless.

This is why guys at OpenAI released the Gym toolkit back in 2016. OpenAIs’s gym offers a standardized API for a collection of environments for different problems, including

- the classic Atari games,

- robotic arms

- or landing on the Moon (well, a simplified one)

There are proprietary environments, too, like MuJoCo (recently bought by DeepMind). MuJoCo is an environment where you can solve continuous control tasks in 3D, like learning to walk.

OpenAI Gym also defines a standard API to build environments, allowing third parties (like you) to create and make your environments available to others.

If you are interested in self-driving cars, then you should check out CARLA, the most popular open urban driving simulator.

4. Python boilerplate code

You might be thinking:

What we covered so far is interesting, but how do I actually write all this in Python?

And I completely agree with you

Let’s see how all this looks like in Python.

Did you find something unclear in this code?

What about line 23? What is this epsilon?

Don’t panic. I didn’t mention this before, but I won’t leave you without an explanation.

Epsilon is a key parameter to ensure our agent explores the environment enough before drawing definite conclusions on what is the best action to take in each state.

It is a value between 0 and 1, and it represents the probability the agent chooses a random action instead of what she thinks is the best one.

This tradeoff between exploring new strategies vs. sticking to already known ones is called the exploration-exploitation problem. This is a key ingredient in RL problems and something that distinguishes RL problems from supervised machine learning.

Technically speaking, we want the agent to find the global optimum, not a local one.

It is good practice to start your training with a large value (e.g., 50%) and progressively decrease after each episode. This way, the agent explores a lot at the beginning and less as it perfects its strategy.

5. Recap and homework

The key takeaways for this 1st part are:

- Every RL problem has an agent (or agents), environment, actions, states, and rewards.

- The agent sequentially takes actions with the goal of maximizing total rewards. For that, it needs to find the optimal policy.

- Value functions are useful as they give us an alternative path to find the optimal policy.

- In practice, you need to try different RL algorithms for your problem and see what works best.

- RL agents need a lot of training data to learn. OpenAI gym is a great tool to re-use and create your environments.

- Exploration vs. exploitation is necessary when training RL agents to ensure the agent does not get stuck in local optimums.

A course without a bit of homework would not be a course.

I want you to pick a real-world problem that interests you and that you could model and solve using reinforcement learning.

Define what are the agent(s), actions, states, and rewards.

Feel free to send me an e-mail at plabartabajo@gmail.com with your problem, and I can give you feedback.

Original. Reposted with permission.