Introduction to Active Learning

An extensive overview of Active Learning, with an explanation into how it works and can assist with data labeling, as well as its performance and potential limitations.

By Jennifer Prendki, VP of Machine Learning, Figure Eight

As data gets cheaper and cheaper to collect and store, data scientists are left with more data to deal with that they will ever be capable of analyzing. And this trend doesn’t show signs of slowing down: the explosion of IoT devices paired with the appearance of new memory-greedy data formats are leaving data professionals fending for themselves in an ocean of raw data.

Given that the most exciting advances in machine learning require large volumes of data, this is an exciting time. But it also raises a brand new challenge for the ML community: unless the data is labelled, it remains essentially useless for all ML applications relying on a supervised learning approach.

Data labeling: the new bottleneck in Machine Learning

Some of the most promising advances in AI over the last decade have come from the usage of deep learning models. While neural networks were discovered decades ago, their practical use was enabled only recently thanks to the increase in both the volume of data available and in compute power that older hardware simply could not provide. And because most deep learning algorithms use a supervised approach while being data-greedy, the new bottleneck in machine learning nowadays is not about the collection of data anymore, but about the speed and accuracy of the labeling process. After all, most of us are familiar with the axiom, “garbage in, garbage out.” The performance of a model will ultimately suffer unless you have high quality data to train that model on.

Since obtaining an unlabeled instance is essentially free nowadays, winning the AI race now comes down to having the fastest, most scalable, flexible and reliable way to obtain quality labels for your dataset. Labeling high volumes of data has become a critical issue ever since the volume of data to label has become so large that even all human labor on the planet would not be sufficient to meet the need. For example, even at a rate of a few seconds per bounding box, annotating pedestrians on a 10-second video could take several hours for a human alone, which is why more and more companies are now focusing on building machine learning algorithms to automate the annotation process. A human-only approach simply isn’t scalable.

But the sheer volume of data is not the only problem. Getting labels is also often time-consuming (for example, when annotators are asked about the topic of a longer document), often error-prone (and sometimes subjective), expensive (for example, “annotating” a patient record as a positive case of cancer might require a MRI scan or some other costly medical tests, or validating the presence of oil might require drilling), or even plain dangerous (for example, in the case of landmine field detection).

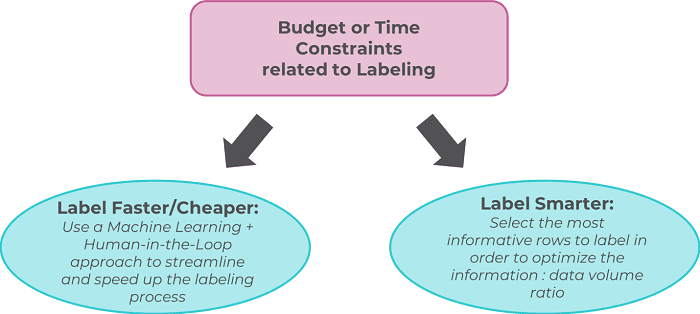

Labeling faster vs. labeling smarter

To address the exploding need in quality annotations, a Human-in-the-Loop AI approach where a human annotator validates the output of a machine learning algorithm seems like a promising approach. Not only does it enable a faster process, it also helps with quality, since the human intervention helps make up for the inaccuracy of the algorithm.

But while this brute-force approach is sometimes the best way forward, another one is slowly gaining more traction among the ML community: the concept of labeling only the data instances that matter the most. As data scientists, we have been trained to think that more data equates a high model accuracy, but while this is absolutely true, it is also important to acknowledge that not all data is created equal because not all examples carry the same quantity of information.

Figure 1: The two ways to address the dawning Big Labeling crisis

Identifying the best instances for a model to learn from can happen at two different times: either before the model is even being built, or while the model is trained. The former is often referred to as prioritization, while the latter is called Active Learning.

What is Active Learning?

In spite of its low coverage in popular ML blogs, Active Learning is actually surprisingly well-motivated in many modern ML problems, in particular when labels are difficult, time-consuming, or expensive to collect.

In Active Learning, the learning algorithm is allowed to proactively select the subset of available examples to be labeled next from a pool of yet unlabeled instances. The fundamental belief behind the concept is that a Machine Learning algorithm could potentially achieve a better accuracy while using fewer training labels if it were allowed to choose the data it wants to learn from. Such an algorithm is referred to as an active learner. Active learners are allowed to dynamically pose queries during the training process, usually in the form of unlabeled data instances to be labeled by what is called an oracle, usually a human annotator. As such, active learning is one of the most powerful examples of the success of the Human-in-the-Loop paradigm.

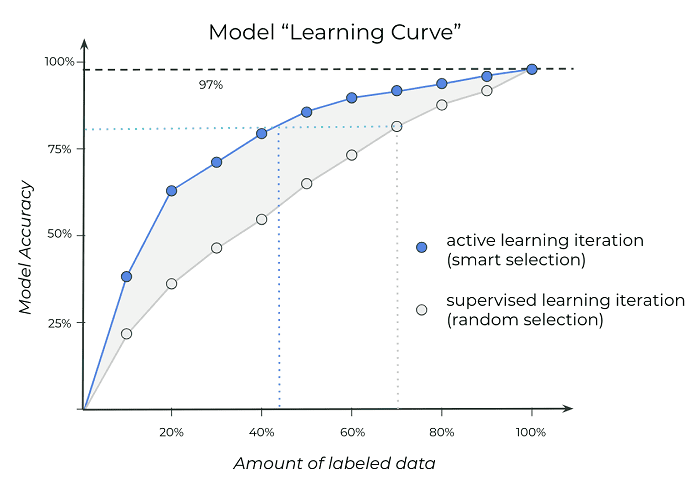

Figure 2: As expected, the more data available to train a model, the higher the accuracy regardless of whether or not an Active Learning approach is used. However, with Active Learning, a given accuracy can be reached with significantly less data; in this example, a 80% accuracy can be achieved with only 45% of the total volume of available data as opposed to 70% in the case of regular supervised learning.

How does Active Learning work?

Active Learning can be implemented through different scenarios. In essence, deciding whether or not to query a specific label comes down to deciding whether the gain from obtaining the label offsets the cost of collecting that information. In practice, making that decision can take several forms depending on whether the scientist has a limited budget or simply tries to minimize his/her labeling bill. Overall, three different categories of active learning can be listed:

- The stream-based selective sampling scenario, which consists in determining if it would be sufficiently beneficial to enquire for the label of a specific unlabeled entry in the dataset. As the model is being trained and is presented with a data instance, it immediately decides if it wants to see the label. The disadvantage of that approach naturally comes from the absence of guarantee that the data scientist will stay within his/her budget.

- The pool-based sampling scenario is also the best-known one. It attempts to evaluate the entire dataset before selecting the best query, or a set of best queries. The active learner is usually initially trained on a fully labeled fraction of the data which generates a first version of the model which is subsequently used to identify which instances would be the most beneficial to inject in the training set for the next iteration (or active learning loop). One of its biggest downsides comes from its memory-greediness.

- The membership query synthesis scenario might not be applicable to all cases as it implies the generation of synthetic data. In this scenario, the learner is allowed to construct its own examples for labeling. This approach is promising to solve cold-start problems (like in search) when generating a data instance is easy to do.

How is active learning different than reinforcement learning?

Although both reinforcement and active learning can reduce the number of required labels for your models, they are very different concepts.

On the one hand, we have reinforcement learning. Reinforcement learning is a goal-oriented learning approach inspired by behavioral psychology that allows you to take inputs from the environment. As such, reinforcement learning implies that the agent will get better as it is in use: it learns while in usage. When we humans learn from our mistakes, we are actually functioning through a reinforcement learning approach. There is no actual training phase; instead the agent learns through trial-and-error using a predetermined reward function that sends back the input about how optimal a specific action it took turned out to be. Technically, reinforcement learning does not need to be fed with data, but instead generates its own as it goes.

Active learning, on the other end, is closer to traditional supervised learning. It is, in fact, a type of semi-supervised learning (where both labeled and unlabeled data is used). The idea behind the concept is that not all data is created equal, and that labeling just a small sample of data might get to the same accuracy (if not hire), the only challenge being to identify what that sample is. Active learning is about incrementally and dynamically labeling data during the training phase in order to allow the algorithm to identify what label would be the most informational for it to learn faster.

How to decide which row to label?

The approach used to determine which data instance to label next is referred to as a querying strategy. Below, we are listing those that are the most commonly used and studied ones:

Uncertainty sampling

For those querying strategies, a model is first trained on a fairly small sample of labeled data; this model is then applied on the (unlabeled) remainder of the dataset. The algorithm chooses which instances to label over the next active learning loop based on the information it gained through this inference step.

The most popular among those strategies is the least confidence strategy, where the model selects those instances with the lowest confidence level to be labeled next. Another common strategy is called margin sampling: in this case, the algorithm selects the instances where the margin between the two most likely labels is narrow, meaning that the classifier is struggling to differentiate between those two most likely classes. The two strategies aim at helping the model discriminate among specific classes and overall do a great job reducing specific classification error. However, if the objective function consists of reducing log-loss, an entropy-based where the learner simply queries the unlabeled instance for which the model has the highest output variance in its prediction, is usually more appropriate.

Query-by-Committee (aka, QBC)

With those strategies, a committee of different models is trained on the same labeled training set and used for inference on the rest of the (yet unlabeled) data. The instances for which the largest disagreement is observed are deemed to be the most informative ones. The core idea behind this framework is minimizing the version space, which is the set of hypotheses that are consistent with the current labeled training data.

Expected Impact

Those querying strategies examine the impact of the addition of new labels on the overall performance of the model. The expected model change strategy aims at identifying the instances that would lead to the biggest change to the current model should the labels for those instances be known. The expected error reduction strategy measures not how much the model is likely to change, but how much its generalization error is likely to be reduced. One challenge with that strategy is that it is also the most computationally expensive query framework. And because minimizing an expected loss function usually doesn’t have a close form solution, a variance reduction approach is used as a proxy.

Overall, these methodologies look at the input space as a whole rather than focusing on individual instances as uncertainty sampling or QBC would, which gives them the singular advantage to be less prone to selecting outliers.

Density-Weighted Methods

The previous frameworks describe strategies that identify the most informative instances as being those with a highest level of uncertainty. However, another way to look at the problem is to consider that the most valuable instances in a dataset are not necessarily those for which the uncertainty is maximal, but rather those which are the most representative of the underlying distribution of the data: this is what the information density framework is all about.

Performance & Limitations

More than 9 researchers out of 10 who have attempted some work involving Active Learning claim that their expectations were met either fully or partially. That’s very encouraging, but one can’t help but wonder what happened in the other cases.

The truth here is that Active Learning is still not well understood. There is some promising work on deep active learning for NER for example, but many of the large questions remain. There is very little work, for example, on predicting ahead of time if a specific task or dataset is particularly prone to benefit from an active learning approach.

Ultimately, Active Learning is a particular case of semi-supervised learning, a category of algorithms which has been shown to be highly vulnerable to biases, in particular because they are at risk of self-indulging in initial beliefs derived from the patterns identified by a model trained on a fairly small dataset. With the efficient labeling becoming an ever-more critical component of Machine Learning, it is to be expected that a lot more research on the topic will be published in the coming years.

Bio: Jennifer Prendki is a Data Science Leader and a Data Strategist, who takes great pleasure in envisioning the future of Data Science and evangelizing it. Jennifer is particularly skilled in growing and managing early-stage data teams, and is highly comfortable managing hybrid teams, including product managers, data scientists, data analysts and engineers across the board (Front-End, Backend, Systems, etc.)

Related:

- How to Put Active Learning to Work for Your Enterprise

- The Essential Guide to Training Data for Machine Learning

- The 2018 Data Scientist Report is Here