The Emergence of Cooperative and Competitive AI Agents

Without specific training in collaboration or competition, a recent AI model from DeepMind uses reinforcement learning to evolve these behaviors in game-playing agents. Learn how this emergent collective intelligence outperforms their human counterparts in 3D multiplayer games.

Collaboration and competition are two of the key pillars on the evolution of human societies and essential to our evolution as species. Billions of people inhabit our planet grouped in millions of communities, each with their own beliefs about politics, economics, religion, social justice, or sports. While those beliefs make each of us unique, they haven’t prevented us from coming together to achieve amazing things. Those group efforts are typically guided by the cooperative and competitive dynamics between its members who constitute the foundation of collective intelligence. From this perspective, every area of human knowledge can be traced back to a collaborative and/or competitive dynamic in a specific community. In artificial intelligence (AI), most of the recent breakthroughs have been constrained to individual agents operating in highly constrained environments. Enabling collective knowledge building dynamics is essential to the evolution of AI, and it requires fomenting organic competition and collaboration between AI agents. Recently, Science published a paper from Google’s subsidiary DeepMind highlighting their fascinating experiences building collaboration and competition in AI agents playing the Quake III Capture the Flag (CTF) game.

Among the fast-growing ecosystem of AI subdisciplines, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) is the one that provides the best environment for the evaluation of competitive and collaborative dynamics between AI agents. In a MARL setting, different agents need to explore a given environment in order to achieve a specific goal without any prior training. In other words, they need to learn the dynamics of the environment by trial and error while cooperating and competing with other agents. Multi-player games provide a great setting for MARL agents and, among those, CTF has been rated one of the most challenging environments for AI agents ever conceived.

CTF presents a unique balance between a relatively simple set of rules and incredibly complex environment dynamics. In a CTF game, two teams of individual players compete on a given map with the goal of capturing the opponent team’s flag while protecting their own. To gain a tactical advantage, they can tag the opponent team members to send them back to their spawn points. The team with the most flag captures after five minutes wins. To be successful, players need to cooperate and compete with their teammates and opposing team, respectively, while constantly adapting to the changing dynamics of the game.

For the Win Architecture

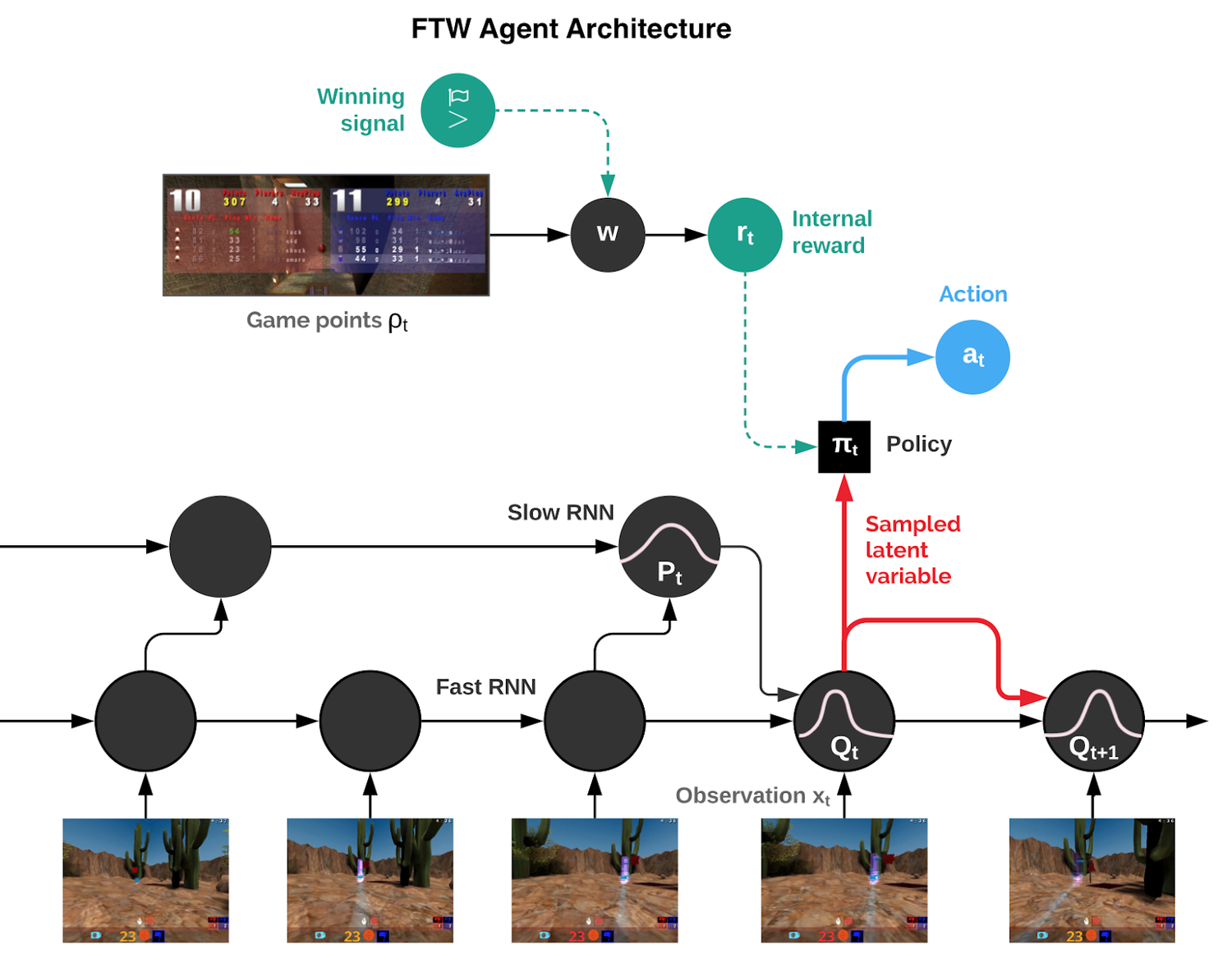

To address some of the difficult challenges of the CTF environment, the DeepMind team relied on a clever MARL architecture they called For the Win (FTW). The architecture extends some of the principles of traditional MARL models with a series of unique principles optimized for CFT dynamics:

- Rather than training a single agent, the FTW model trains a population of agents, which learn by playing with each other, providing a diversity of teammates and opponents.

- Each agent in the population learns its own internal reward signal, which allows agents to generate their own internal goals, such as capturing a flag. A two-tier process optimizes agents’ internal rewards directly for winning and uses reinforcement learning on the internal rewards to learn the agents’ policies.

- Agents operate at two timescales, fast and slow, which improves their ability to use memory and generate consistent action sequences.

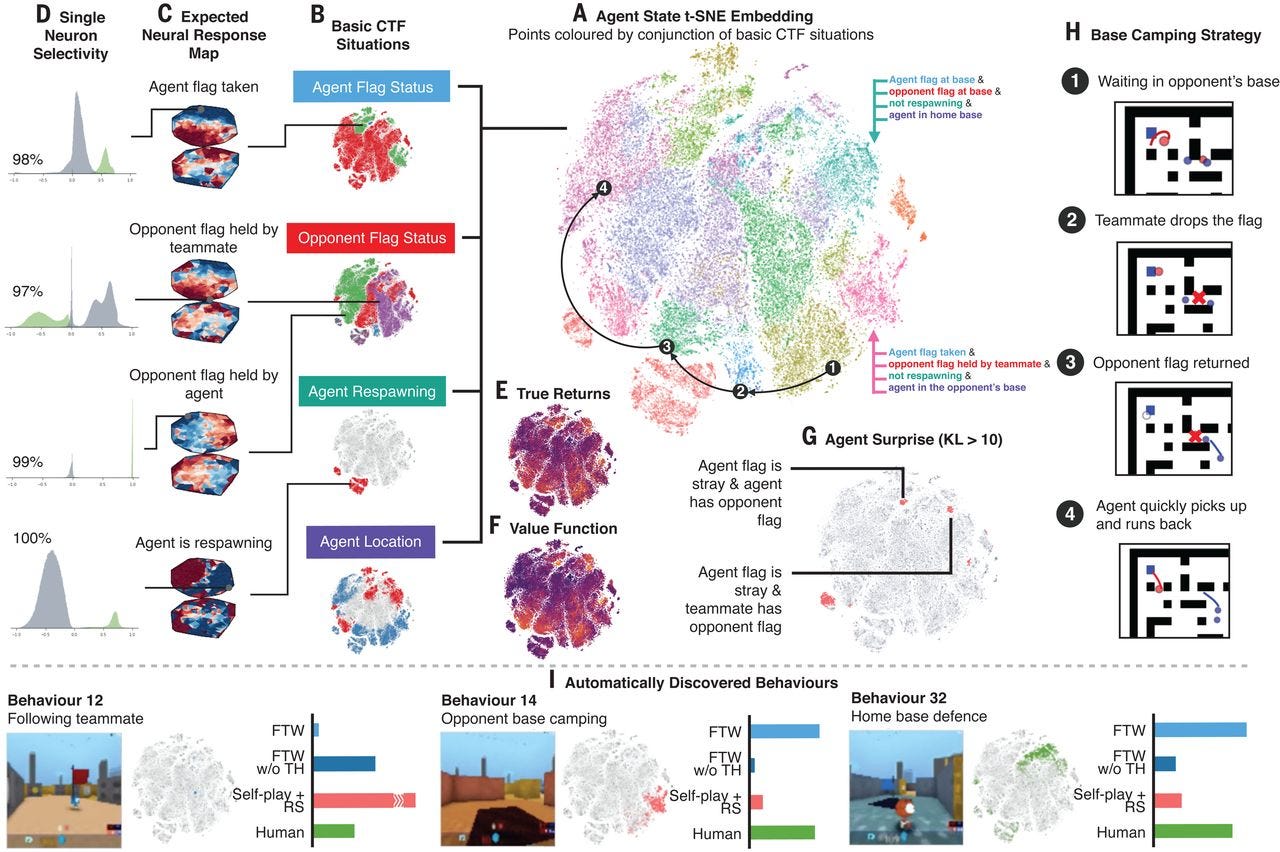

In the FTW architecture, agents need to quickly learn to cooperate and compete with other agents as well as human players. In order to achieve that, the MARL agents need to build a rich representation of the environment in a way that facilitates both competitive and collaborative dynamics. To validate this assumption, the DeepMind team modeled the environment representation of a given agent using about 200 features that accurately describe its perspective of the state of the game. Features include questions such as “Do I have the flag?”, “Did I see my teammate recently?”, and “Will I be in the opponent’s base soon?”. As you can see, some of these features clearly indicate competitive (opponent) or collaborative (teammate) associations. The experiments showed that agents were able to learn competitive and collaborative relationships particularly well. Looking at the acquisition of knowledge as training progresses, the agents first learned about its own base, then about the opponent’s base, and then about picking up the flag. Immediately, useful flag knowledge was learned before knowledge related to tagging or their teammate’s situation.

The dynamics of the agents in the FTW model are clearly explained by visualizing their activation patterns of the neural network. In the following visual, clusters of dots in the figure below represent situations during play with nearby dots representing similar activation patterns. These dots are colored according to the high-level CTF game state in which the agent finds itself: In which room is the agent? What is the status of the flags? What teammates and opponents can be seen? We observe clusters of the same color, indicating that the agent represents similar high-level game states in a similar manner.

A key thing to highlight is that agents in the FTW model are never trained in collaborative or competitive dynamics. The behavior of the agents is purely a result of constantly playing the game with other agents and human players.

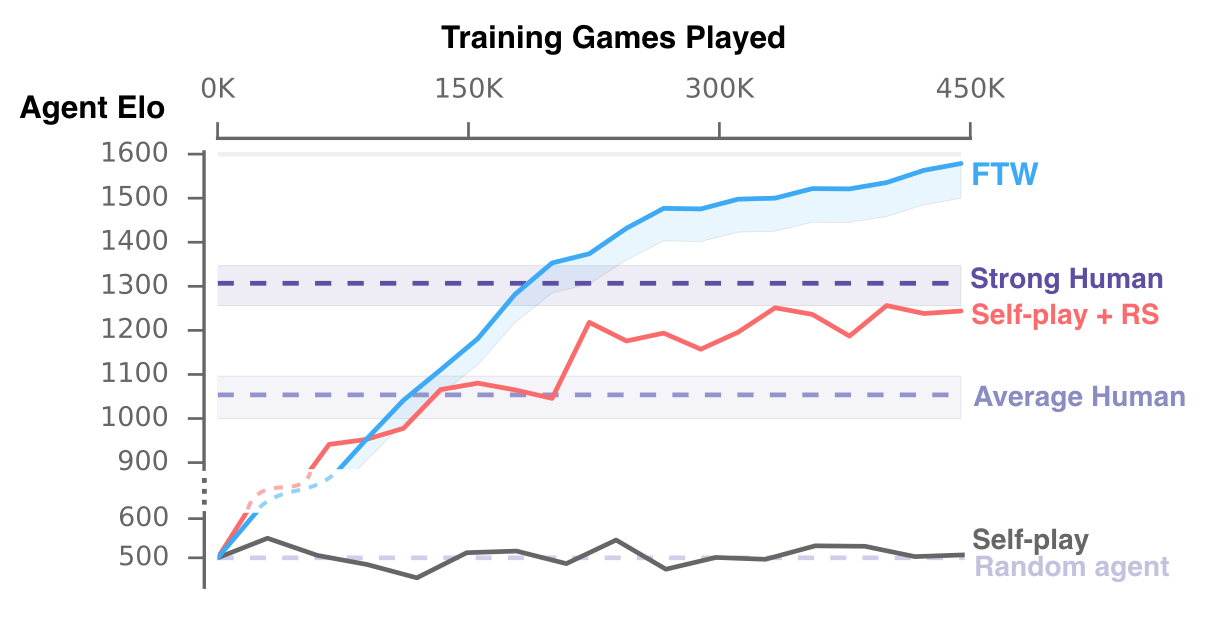

Collaboration and Competition in Action

To evaluate the collaborative and competitive behaviors of the FTW agents, the DeepMind team performed a large tournament on procedurally generated maps with ad hoc matches that involved three types of agents as teammates and opponents: ablated versions of FTW (including state-of-the-art baselines), Quake III Arena scripted bots of various levels, and human participants with first-person video game experience. The FTW agents didn’t only exceed the win-rate of human players in environments never seen before, but they also proved to be more collaborative than human participants. The DeepMind team wanted to challenge this surprising result and create a new challenge with a team of two professional games testers with full communication to play continuously against a fixed pair of FTW agents. Even after 12 hours of practice, the human game testers were only able to win 25% (6.3% draw rate) of games against the agent team.

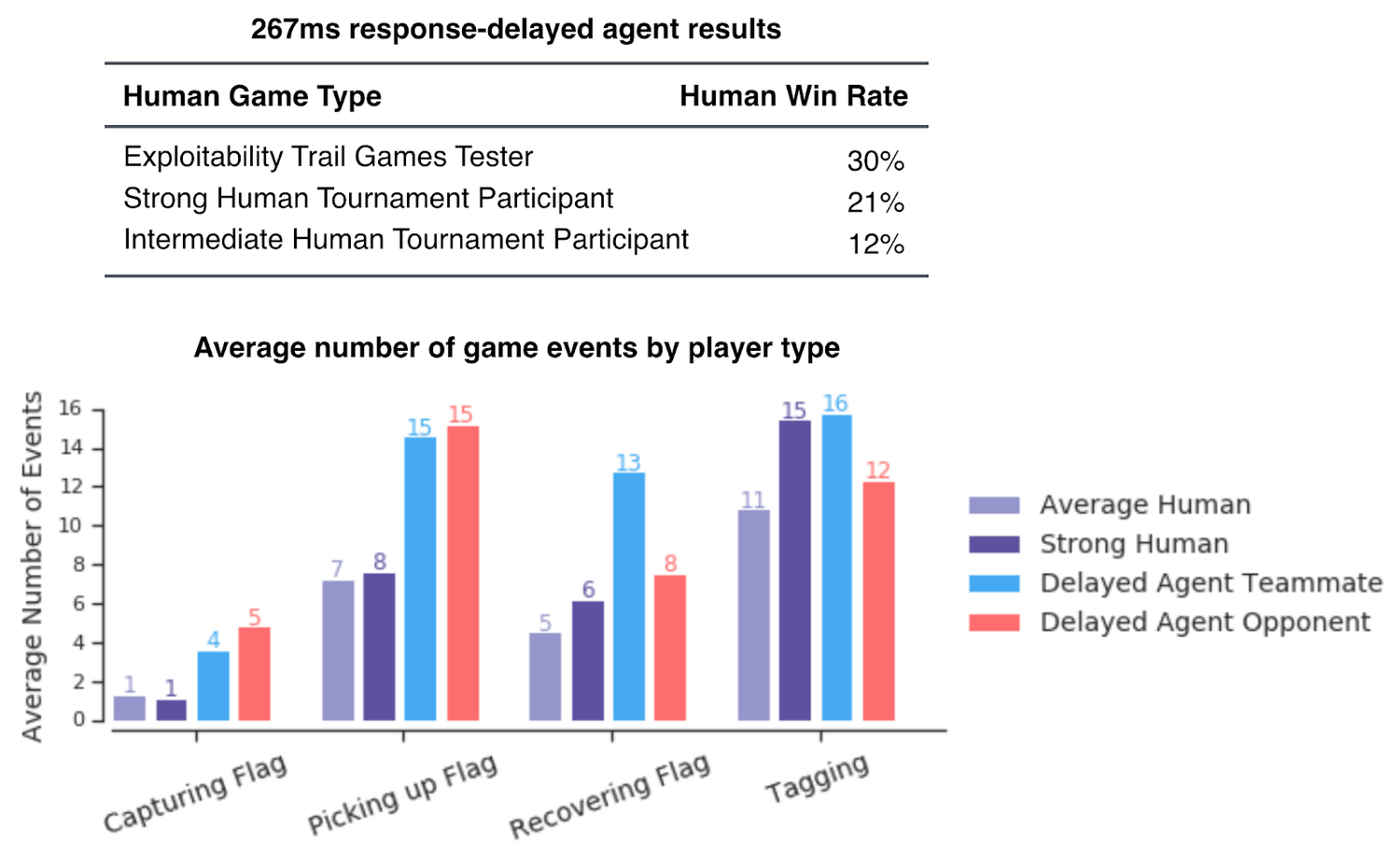

A potential explanation for the superior performance of the FTW agents is their faster visual and motor control compared to human players. To discard this, the DeepMind team introduced random delays in the agent’s reaction time. Even after this, the FTW agents were able to outperform the strongest human players most of the time.

One of the fascinating things discovered in the FTW tests was the emergence of human-like collaborative and cooperative behaviors such as following teammates and camping in the opponent’s base. Even more remarkable was to observe how those behaviors evolved over time. For instance, early in the game behaviors such as following a teammate were prevalent, but quickly, it lost relevance as agents learned to cooperate in a more complementary manner.

DeepMind’s FTW showed that multi-agent reinforcement learning models could enable the emergence of collaborative and competitive dynamics between AI agents in ways that even surpass humans counterparts. If we assume that collaboration and competition are the basics of collective intelligence, ideas such as FTW show us that this form of intelligence can evolve organically in AI environments and even adapt to human’s standards.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Bio: Jesus Rodriguez is a technology expert, executive investor, and startup advisor. A software scientist by background, Jesus is an internationally recognized speaker and author with contributions that include hundreds of articles and presentations at industry conferences. Jesus is a board member of several enterprise software companies like Electric Cloud and Mobiquity and also serves as an advisor to companies such as Microsoft and Oracle.

Related: